While “scientific consensus” on climate change may sound like an oxymoron, there is consensus on three key questions about climate change and hurricanes, as demonstrated by recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Executive Summary

According to scientific consensus, there is no detectable link between human activity and hurricane activity, says Karen Clark, interpreting the IPCC’s most recent report. Looking ahead, however, anthropogenic climate change could lower the frequency of storms. And with wind speeds of hurricanes jumping 2-11 percent, insurance losses for each storm will be higher, she notes.The IPCC, the scientific body under the auspices of the United Nations that reviews and assesses the scientific, technical and socio-economic information produced by thousands of scientists around the world, has recently released its Fifth Assessment Report.

The summary of the report (reference 1 at the bottom of this article) along with an earlier Special Report on Extreme Events (reference 2) contain a synthesis and distillation of the current science, the climate model results and the global scientific opinion on climate change and its likely impacts.

Because of the potential impact on losses, insurers and reinsurers are keenly interested in the relationship between global warming and hurricane activity, but there is a lot of misunderstanding and misinformation surrounding this topic. This article reviews the current scientific consensus on whether human activity has already had an impact on hurricanes, what impacts anthropogenic warming are likely to have on hurricane activity in the 21st century, and what this means for insurers and insured losses.

Has human-induced climate change already impacted hurricane activity?

Despite popular belief that recent events are “proof” anthropogenic climate change is causing more hurricanes, the scientific consensus is the opposite. Given the current state of knowledge, scientists cannot conclude that human activities have had any influence on hurricane activity to date. According to the IPCC, “There is low confidence in any observed long-term increases in tropical cyclone activity (i.e., intensity, frequency, duration) after accounting for past changes in observing capabilities.”

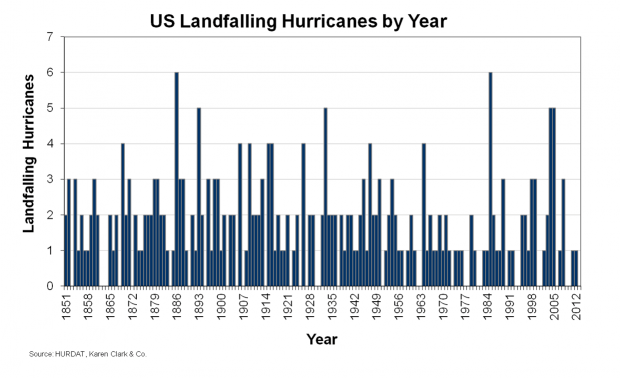

While simple plots of the annual number of tropical cyclones since 1851 seem to indicate a significantly increasing trend, scientists have concluded that there is no real trend and that observational biases are responsible for the apparent increases in the number of storms. In other words, with aircraft and satellite technology scientists are detecting more storms now than they did decades ago under a ship-based observation network.

These conclusions are consistent with the data on hurricanes as well as U.S. landfalling hurricanes, neither of which show upward trends over the past century.

What about storm intensity?

While the data seem to suggest we’re experiencing more major (Category 3, 4 and 5) hurricanes over the past few decades, there is scientific disagreement over what is causing the increase—internal variability, human influences (anthropogenic forcings) or natural forcings. For example, according to the IPCC, for the North Atlantic basin there is medium confidence that a reduction in aerosol forcing (versus greenhouse forcing) has contributed to the observed increase in tropical cyclone activity since the 1970s.

Natural external forcings include changes in solar radiation and volcanism.

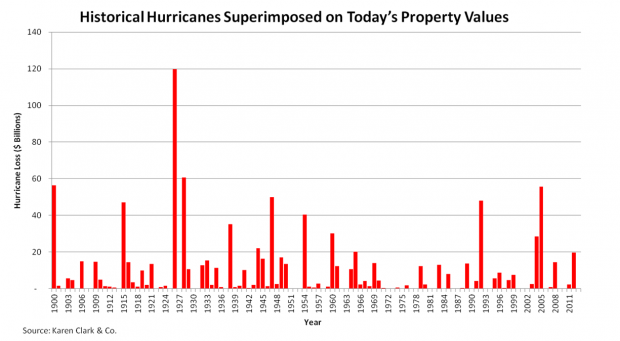

With respect to hurricane losses, there is scientific agreement that, to date, the most significant driver of increasing losses is increasing property values in hazardous coastal areas. According to the IPCC, “Increasing exposure of people and economic assets has been the major cause of long-term increases in economic losses from weather and climate-related disasters (high confidence).”

Karen Clark & Co. recently conducted a study of historical U.S. hurricanes and what they would cost today given current property values. The results shown in the chart below confirm there is no increasing trend in losses over time, which is consistent with scientific opinion.

Globally, there is low confidence in the attribution of changes in tropical cyclone activity to human influence. We cannot rule out human influences, but if human activities have had an impact, it’s not yet detectable in the data.

What impacts will climate change have on future hurricane activity in the 21st century?

Here again, part of the answer may be surprising. Based on results from the most sophisticated climate models, it is likely that the global frequency of tropical cyclones will either decrease or remain essentially unchanged.

The reason for this counterintuitive result is that even though sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are likely to warm dramatically during the 21st century, the upper tropospheric temperatures are likely to warm even more. Additionally, most of the climate models project increasing levels of vertical wind shear over parts of the tropical Atlantic. Increased warming of the upper troposphere relative to the surface and increased vertical wind shear are both detrimental factors for storm development and intensification.

Why does increased warming of the upper troposphere relative to the surface inhibit hurricane formation?

In the lower troposphere, air spirals inward toward the center of the hurricane, then upward in the eyewall and then outward at the top of the troposphere. The air eventually sinks back toward the lower troposphere and the circulation continues. This secondary circulation works like a heat engine and requires air to flow into the hurricane in the lower troposphere at a higher temperature than it exits the hurricane at the top of the troposphere.

Fast, upper tropospheric winds can also create high values of vertical wind shear, a change in wind direction or speed at different altitudes.

With respect to storm intensity, the scientific consensus is more intuitive. “Average tropical cyclone maximum wind speed is likely to increase, although increases may not occur in all ocean basins.”

This is more likely to occur in the latter part of this century—2081 to 2100.

According to the climate models, by the end of the 21st century, hurricanes could be more intense with maximum wind speeds 2-11 percent higher than the current reference period.

Anthropogenic warming over this century may also lead to an increase in the number of very intense (Category 4 and 5) hurricanes in some basins. The climate models also project substantially higher rainfall rates than present day hurricanes.

What is the likely trend in insured hurricane losses?

Over the past century, the primary driver of increasing insured hurricane losses has been rising property values along vulnerable coastlines. Over the past few decades, U.S. hurricane losses have about doubled every 10 years due to demographic factors.

It is very likely that if unmitigated, these demographic trends will continue to drive up insured losses well into this century, and the most effective ways to control the rising costs of hurricanes would be to implement and enforce better building codes and land-use planning strategies.

By the end of the 21st century, climate change will likely be having a significant impact on hurricane losses. Losses increase exponentially with wind speeds, so even a 2 percent change in maximum wind speeds can lead to a 10 percent increase in losses. An 11 percent increase in peak winds would result in expected losses more than 50 percent higher than today.

All projections are for continued sea level rise that will subject coastal properties to higher wind speeds from landfalling hurricanes along with making the properties more vulnerable to storm surge flooding.

In summary, according to the most recent scientific consensus, human activity has of yet had no detectable influence on hurricane activity. Anthropogenic climate change is likely to impact hurricane activity later in the 21st century. The frequency of storms is likely to decrease or remain the same, but hurricanes are likely to become more intense—possibly with maximum wind speeds 2-11 percent higher by the end of the century.

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit  Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid  Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers

Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash