While most homeowners and commercial property owners may not purchase earthquake insurance, standard insurance policies provide coverage for fire damage, including any fire losses that may result from earthquakes. So, private insurers are generally more concerned about potential fire following losses than earthquake shake losses.

The idea that fires following earthquakes could cause mega-losses to insurers gained prominence after a 1987 Insurance Research Council study on the potential losses. The study concluded that major earthquakes in the Los Angeles Basin and the San Francisco Bay area would be likely to cause major conflagrations, generating fire damage and insured losses of $4 billion and $17 billion, respectively, which would equate to nearly $15 billion and $65 billion today based on increases in population and property replacement values.

It’s been almost 40 years since this study, and there have been no major fire following earthquake losses in the U.S. This article explains why and illustrates the risk of fire following earthquake losses today.

Fire Losses Resulting From Historical Earthquakes in the U.S.

The poster child for devasting fire following earthquake losses is the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. Images and reports from the 1906 earthquake show that much of the devastation was caused not by the ground motion directly but by the fires that broke out after the earthquake. These fires resulted in major conflagrations and extensive property damage across the city.

Many of the fires in the 1906 event were the result of collapsed buildings. When buildings collapse, the gas lines to the structures can rupture. Leaking gas can quickly fill the space and even a small spark from short circuits, exposed wiring or a running appliance can ignite it.

Along with building collapse, cooking fires resulted in conflagrations in the 1906 event. The most famous of these is the “Ham and Egg Fire,” which ignited when a woman started cooking breakfast on a gas stove unaware that her chimney had been damaged by the earthquake earlier that morning.

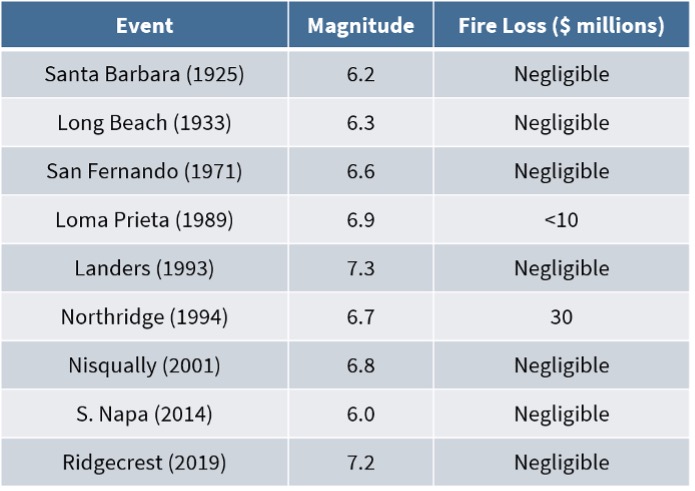

Since 1906, no earthquake has caused significant fire losses in the U.S., as shown in the table below.

The Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989 resulted in several fires, but apart from the Marina Fire which destroyed a large apartment building, all other fires were easily extinguished. The Northridge Earthquake in 1994 resulted in over 100 ignitions in the San Fernando area, but most of these were in mobile home parks. Many manufactured homes are built on support piers of steel or masonry. Historically, these piers were constructed to resist gravity loads but not lateral loads, so they could not support the homes during the earthquake. The collapsed mobile homes ruptured gas lines, which led to most of the ignitions. Outside of mobile home parks, one major fire broke out on Balboa Boulevard when the underlying gas main broke, but only five homes were lost in that fire.

What would it take to have a large fire following loss today?

The data show much has changed since 1906, and the risk of fire following losses is much lower today. Stronger building codes prevent most structures from collapsing, and modern gas shut off valves activate automatically in the event of ground shaking. Since Northridge, Calif., has strengthened the codes for manufactured homes. Infrastructure around water supply and suppression activities has been improved over time to account for potential earthquake-induced fires.

It’s much less likely that even a major earthquake would cause a large fire following loss today. In order for that to occur, four things are necessary:

- Very high ground motion

- A densely populated area

- A vulnerable building stock

- Major disruption to infrastructure and water supplies

It’s About Ground Motion, Not Magnitude

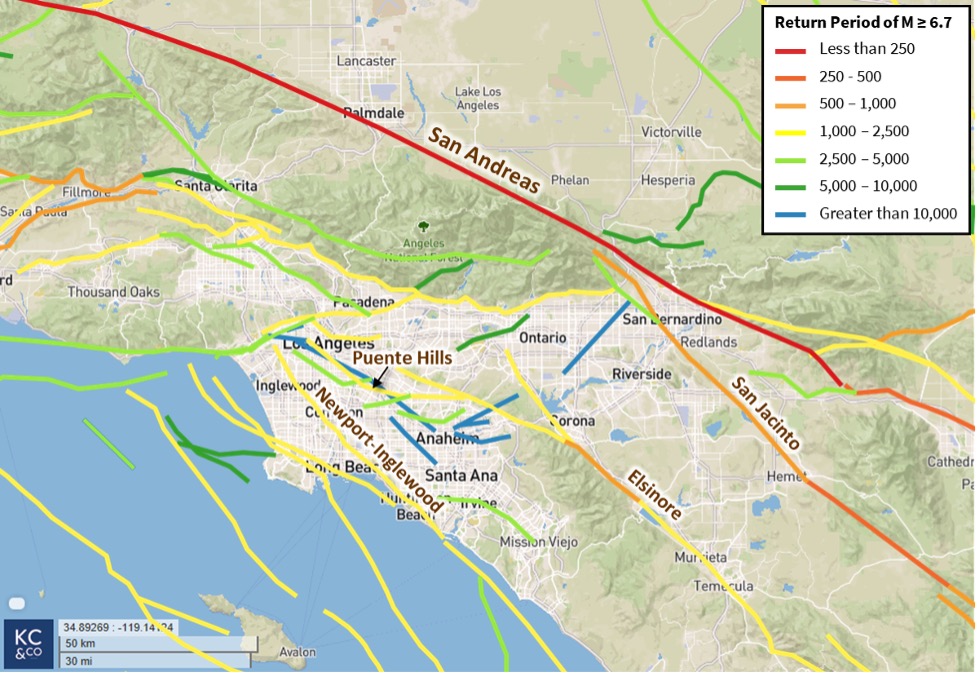

While these factors can all come together after a major earthquake, it’s with a relatively low probability. For example, the Los Angeles area is vulnerable to large magnitude earthquakes generated by the southern segment of the San Andreas fault. But the San Andreas fault is 35 miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles, so even a very large magnitude event would result in only moderate ground motion in the most densely populated areas.

Large magnitude events on faults directly under the most populated areas, such as the Puente Hills fault in Los Angeles, are more likely to cause major fire losses. Even a magnitude 6.7 directly under the city could lead to very high ground shaking and a fire following loss exceeding $50 billion, but the return periods for events of this magnitude on the faults underlying Los Angeles are long—on the order of thousands of years. The image below shows the mapped faults in the Los Angeles area with estimated return periods for a magnitude 6.7 and above.

The San Francisco Bay area is vulnerable to fire following losses due to the proximity to the Hayward and northern sections of the San Andreas Fault. Most homes in these areas are wood frame and many have soft stories that can induce building collapse.

Major earthquakes on the northern section of the San Andreas fault will result in high ground motions in the densely populated areas of San Francisco. Fortunately, San Francisco has achieved substantial progress in seismic retrofitting; under the Earthquake Safety Implementation Program, over 90 percent of the city’s soft-story buildings have been retrofitted.

But several cities in East and South Bay have no mandatory soft-story programs, leaving many soft-story buildings unstrengthened. Because the Hayward fault is believed to be overdue for a major event, and an event on this fault would generate the highest ground motion in the East and South Bay areas/neighborhoods, this is the area most likely to experience a large fire following loss today.

While there are scenarios in California that would lead to fire following losses in the tens of billions of dollars, only extreme scenarios with return periods longer than 500 years are likely to generate losses exceeding $50 billion.

Outside of California

Perhaps surprisingly, outside of California the most vulnerable city to fire following losses is Charleston, S.C. The Charleston seismic zone is the second largest source of major earthquakes in the Central and Eastern U.S.

Outside of California the most vulnerable city to fire following losses is Charleston, S.C.

In 1886, an earthquake with an estimated magnitude between 6.9 and 7.3 devastated the city. Scientists have not been able to identify the specific fault that generated this event, but based on paleoliquefaction studies, scientists have estimated a mean recurrence interval of 500-550 years for a magnitude 7 event in the Charleston seismic zone.

Charleston has a high proportion of buildings that are not designed to withstand major earthquakes, including wood frame homes. A major earthquake would result in high ground motion in the most densely populated areas, likely causing fires that could overwhelm the fire-fighting capabilities of the city.

KCC scientists have estimated that a magnitude 7 earthquake in Charleston could result in fire losses exceeding $10 billion.

What about the New Madrid Seismic Zone?

Scientists believe a major earthquake in this seismic zone would rupture in a relatively sparsely populated area along and just west of the Mississippi River near New Madrid, Mo. Under these scenarios, the closest city to experience moderate to high ground motion would be Memphis. More populated cities, such as St. Louis, would likely only experience low ground motions and only a few fires that would not lead to conflagrations. So, the Central U.S. has a very low probability of major fire following losses.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Cascadia subduction zone can generate large magnitude earthquakes, but because the ruptures are expected to occur offshore, most scenarios produce low to moderate levels of ground shaking in major population centers such as Seattle and Portland.

In summary, while large fire following losses are possible today, the probability is relatively low, even in California. The 1906 Great San Francisco earthquake occurred when there was much less preparation for major earthquakes and fire suppression activities were not adequate to deal with major conflagrations. Of course, insurers should still be prepared for the large losses that could occur, and the catastrophe models can help identify where individual companies may be most exposed.

Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers

Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers  RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit  Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster  Earnings Wrap-Up: AXIS Expanding Insurance Biz, Shrinking Re Book

Earnings Wrap-Up: AXIS Expanding Insurance Biz, Shrinking Re Book