The 2021 wildfire season in the Western United States was another one for the books, breaking records for size and destruction right up to the last day of the year.

Executive Summary

Verisk Senior Scientist Philip Cunningham describes conditions conducive to wildfires—periods of precipitation sufficient to grow vegetation, followed by long periods of drought conditions and high “vapor pressure deficit,” strong winds and ignition sources—and how they all came together to produce a record-breaking season in 2021. Across much of the U.S., not only are fire seasons getting longer, but longer fire seasons are becoming more frequent, he writes, also noting that fewer but larger fires were evident in 2021—continuing a multidecadal trend.The last wildfires of 2021 were two grass fires that started in Boulder County, Colo., late in the morning of Dec. 30. The first, the Middle Fork Fire, was contained later that day without damage to structures, but the second, the Marshall Fire, was dramatically different. Fueled by extreme winds, with gusts reported as high as 115 mph, this fire spread quickly and within two days had destroyed more than 1,000 buildings and damaged more than 100 others, setting a new state record for structures lost. Tragically, two people were killed.

The intensity of the Marshall Fire was driven by high winds but also by a significant amount of fuel in the form of dry grass. While the dry summer and fall in Boulder County led to especially flammable biomass, the wet spring may have supported above-average grass growth and production of that eventual fuel. Nevertheless, under the extreme wind conditions experienced during the Marshall Fire, almost any level of fuel could have supported a devastating fire once ignited.

A Look Back

In the Western United States, a heat wave in June and drought conditions that started in early summer and continued through the fall made 2021 particularly vulnerable to wildfires and for a longer period than average. Across much of the U.S., not only are fire seasons getting longer, but longer fire seasons are becoming more frequent. This means we are seeing wildfires earlier and later than we used to, including during winter months—as was the case with the Marshall Fire.

A strong connection between weather conditions and burned area suggests that climate change over recent decades has contributed, at least in part, to increased wildfire activity in some areas of the Western United States. Attributing any individual wildfire to climate change, however, is particularly challenging, given the many other complicating influences involved; these include ignition factors and human activity (e.g., construction, forest management practices), along with the effects of natural climate variability (e.g., El Niño/Southern Oscillation).

A key element of what enables the ignition and spread of wildfires is the environment in which they occur. Wildfires commonly occur in areas where the climate provides sufficient precipitation for various types of vegetation to grow, yet also experiences extended periods of relatively low humidity and high temperatures. Wet periods provide an ample growing season to accumulate fuels, while relative hot and arid periods dry out the vegetation, making it flammable.

This pattern is apparent in the Western United States, as many parts receive sufficient precipitation to support vegetation growth but also experience extended warm, dry seasons. In addition, the various mountain ranges are conducive to strong local and regional wind patterns; given an ignition source and sufficient fuels, these sustained winds help wildfires develop and spread.

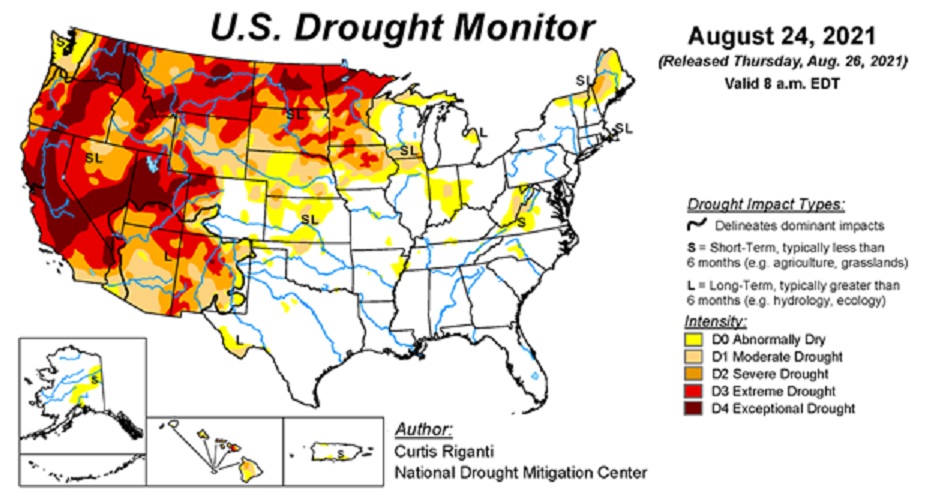

This fire environment was a critical factor during 2021, as around 40 percent of the country was experiencing drought conditions by the end of August and more than half of California was experiencing exceptional drought (Graph below).

Drought conditions and a high vapor pressure deficit (VPD)—a measure of how far the atmosphere is from being saturated—led to a drier fuel load (i.e., the total amount of combustible material in an area), which in turn increased flammability. There is a positive correlation between fire and VPD, especially in forested areas. VPD has been increasing in the recent historical past, as has burned area.

According to the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), the average number of acres burned in the United States from 1991 to 2000 was 3,600,745; that number increased by 57 percent to 5,645,650 for 2001-2010, and by a further 33 percent to 7,516,819 for 2011-2020. A recent Verisk study published by the Society of Actuaries Research Institute found that burned area is expected to increase significantly by 2050.

Strong winds are also a critical environmental component that drives wildfire risk. Wind speed, direction and seasonality all have an impact on fire growth and movement. Wind can also carry embers onto structures, a phenomenon known as spotting that is a primary cause of structure ignition in fires located where human development meets wildland areas—called the wildland-urban interface, or the WUI.

Extreme fire behavior is almost always associated with strong winds; extreme winds due to a downslope windstorm were responsible for the destructive nature of the Marshall Fire, while in California strong downslope winds, known as Santa Ana and Diablo winds in Southern and Northern California, respectively, fueled major fires in 2020 and 2021.

Environmental conditions alone, however, cannot ignite fires. During the past two decades, about 85 percent of wildfires in the United States were ignited by humans, with the remainder ignited by natural forces, almost always lightning.

Fires ignited by lightning, on average, burn larger areas; they are responsible for almost half the area burned since the year 2000.

Fires ignited by humans are generally started in areas where people live, work, travel, and recreate, and thus might be more quickly identified and in relatively close proximity to available suppression resources with access (i.e., roads) to the fire.

Lightning-ignited fires can often be in more remote areas, which can lead to delays in fire discovery and mean limited access to the site by firefighters.

The WUI, populated areas in the Western United States commonly separated by vast wildlands, some of which comprise forest and grasslands that serve as fuel supplies, is an area at high risk for wildfire. The distances between developed areas can allow wildfires to become quite large before they are reported or suppressed, and fires far removed from developed areas are often not a top priority in firefighting.

The two largest 2021 fires in Colorado were caused by lightning: the Oil Springs Fire that burned 12,600 acres, possibly destroying one structure; and the Morgan Creek Fire that burned over 7,500 acres, without damage to residences. As for the Marshall Fire, it remains under investigation and lightning is not on the current short list of possible causes. One relatively rare cause of wildfires is currently a target of the investigation—fires in underground coal mines or coal seams that can generate enough heat at the surface to ignite dry vegetation.

Across the United States, the number of acres burned in 2021 exceeded the 20-year average by a small margin, but the number of wildfires in 2021 trailed the 20-year average by almost 15 percent. This combination of slightly above average area burned and much lower than average number of fires translated into an above-average fire size for 2021 of more than 121 acres per fire. (Most U.S. wildfires are much smaller than 100 acres and cause no damage to structures.)

The year 2021 continued the multi-decadal trend of fewer, but on average larger, wildfires.

California Again in the Spotlight

As is typical in recent years, wildfire activity in California was record-breaking. The powerline-caused Dixie Fire was the second largest in the last 90 years since reliable records have been kept, having burned over 960,000 acres—within 70,000 acres of the record August Complex Fire started by lightning the year before in 2020. The Dixie Fire was not only the second-largest fire but also ranked #14 in terms of destruction (1,329 structures).

Three other 2021 fires cracked the top 20 largest area burned: the lightning-ignited Monument Fire was in 14th place with 223,000 acres burned; the human-ignited Caldor Fire in 15th place with 221,000 acres burned; and the lightning-ignited River Complex in 17th place with 199,000 acres burned. It is notable that 18 of the top 20 largest fires in California’s recorded history have occurred in the past 20 years, according to CAL FIRE.

Other western states also saw historic fires. For example, the lightning-ignited Bootleg Fire in southern Oregon on July 6, which eventually burned more than 400,000 acres, ranks it as the state’s third largest since the beginning of the 20th century. In addition, many summertime high-temperature records were set across Washington State in 2021 and indeed the total area burned for the year, approximately 675,000 acres, was well above average. One fire—the Schneider Springs Fire— exceeded 100,000 acres; however, the state saw very little loss of property throughout the year.

Fire Size and Property Damage

Large fires aren’t necessarily the most damaging. The Marshall Fire, the most destructive fire in Colorado’s history and the last wildfire of the year, burned about 6,200 acres and destroyed 1,000-plus buildings but is dwarfed in size by the Cameron Peak Fire that burned more than 208,000 acres yet destroyed only 224 residential structures in 2020. The best indicator of damage is not fire size but rather the co-occurrence of wildfires with human-built structures, which typically make up only a small fraction of the total area burned.

According to the NIFC, about 70,000 wildfires occur each year in the United States. Most of these are small fires occurring in remote wildland areas where there is little or no exposure at risk. Of these 70,000 wildfires, on average only about 20 or so result in any significant property loss or impact upon the insurance industry. Despite the huge scale of some fires, there is often little correlation between fire size and property damage, as we have noted. If it reaches them, however, wildfires can cause tremendous damage to exposures in WUI areas.

2022 Wildfire Season Outlook and Beyond

In recent years, the United States has experienced rapid WUI growth—particularly in the western states, according to data from the United States Forest Service. Data suggests an upward trend in insured losses over the last two decades, despite the fact that the frequency of wildfires in the United States has been relatively steady, which indicates that the increase in insured losses from wildfires is driven primarily by an increase in the number and value of exposed properties in high-risk areas.

Although no one can predict the future, it is notable that California’s wildfire season has already begun with the Emerald Fire in Orange County, ignited by an unknown cause on February 10 amid unseasonably high temperatures in the 80s and 90s and high winds. This fire grew to an above-average size of 154 acres and was 90 percent contained a few days later without having caused damage to property. As Orange County Fire Authority Chief Brian Fennessy told reporters on the day this fire started, “We no longer have a fire season. We have a fire year.” (Source: Winter wildfire burns Southern California homes,” Associated Press, Feb. 10, 2022)

We will soon see what the rest of 2022 brings in terms of wildfire, but one way to prepare is to use a probabilistic approach that considers today’s environment and conditions to provide a realistic view of wildfire risk not achievable with historical experience alone.

Top photo: AP Photo/Noah Berger

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid  Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook  Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages