Events in 2020 that included protests in response to the brutal killings of several unarmed Black people—George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery to name a few—reignited passionate conversations around systemic racism in North America and across the world. We have had to revisit questions like: Does racism really still exist? To what extent? How is it systemic? And what can we do about it?

Executive Summary

A leader and mentor for the International Association of Black Actuaries shares her experiences and those of other members (with permission) in dealing with racism in and outside the workplace, some research about diversity in the actuarial profession, and IABA recommendations about what white actuaries and other insurance professionals can do to work toward eradicating racism in the P/C insurance industry. “It only requires you to be intentional, vulnerable and open to learning,” she writes, providing a list of dos and don’ts that starts with acknowledging the issue.The first version of this article was originally printed in Future Fellows, September 2020. It is used with permission of the Casualty Actuarial Society.

Even if you wanted to get away from the topic of race, the May incident involving Society of Actuaries member Amy Cooper calling the police on birdwatcher Chris Cooper (coincidental last name) in New York’s Central Park brought this right to our doorstep as actuaries. As an organization whose drive since 1992 has been to increase the number of Black actuaries and provide support to them in overcoming racial barriers to be successful in the profession, the International Association of Black Actuaries (IABA) was primed to further our work with company executives to bring tangible long-term solutions to tackle the issue of racism in the actuarial profession. In fact, over the summer the IABA released a crucial document: a list of recommendations for employers to increase and advance diversity internally.

But where do you personally fit into this grand picture?

That is what I will share with you here. I plan to shed light on the realities of racism in the workplace, why it is important for each of us to address in some way, and how we can do so reasonably and meaningfully.

However, it is important to first note that different Black people have different experiences. For instance, looking at the IABA, our members are truly international, coming from different parts of the world in addition to the U.S. Some are the first in their family to suffer racial discrimination and prejudice in the U.S. or Canada, while others have experienced systemic racism for generations in their families before them. Thus, even though most, if not all, experience some form of racism, the particular experiences and histories differ for different Black actuaries, resulting in different opinions on what action should be taken to eradicate racism.

In writing this article, I intentionally draw not just from my personal experience in working in the U.S. and Canada, but primarily from my involvement with the IABA. As the Toronto Affiliate founder and co-Lead, I am grateful to have been a part of the conversations and work referenced above in addition to participating in conversations and events the IABA has fostered centered on racism in the workplace.

Why Should Racism Matter to You?

It is common industry knowledge today that companies that are more diverse and inclusive have better top- and bottom-line results. (See, for example, “Why Diversity Matters,” McKinsey & Company, 2015). But imagine the impact on personal productivity if you had to endure any of the following real-life examples from actuaries.

Are you a parent? Have you ever wondered, as I have repeatedly, at what point society will change from viewing your children as adorable and cute to viewing them as aggressive threats to be neutralized?

Have you ever considered that one of your team members of color may just unexpectedly not show up to work?

- Nathan Ortiz, ACAS, is frequently stopped by the police for no apparent reason. He often has to prove that he is neither driving a stolen car nor has drugs in his car before the police begrudgingly let him go. Over time, one response he has developed to these incidents is, “Well, this is an interesting reason to be late to work.”

- IABA member and Hartford Affiliate Co-Leader Rodrigue Djikeuchi was arrested in 2015 after a family dinner in town. To this day, he does not know why. He had two flat tires and his insurance company was considerably delayed in assisting him. Hours later he called the police for help. Upon their arrival, they handcuffed him, took him to the local precinct, then transferred him to a county jail for the night. After speaking with the judge the next day, he was let go.

(Editors’ Note: These stories are shared with permission.)

Many Americans read the news in 2018 about Botham Jean, a 26-year-old Black man who was fatally shot and killed while unarmed in his own apartment, when a police officer entered the apartment wrongly believing it to be her own. Jean was an accountant in the Risk Assurance practice of the Dallas office of PwC at the time. Can you imagine the grief of the employees who worked with him?

This is just a small sample of outrageous cases that can have an impact on work outcomes. Some of your colleagues are constantly going through fearful, tormenting and, at times, life-threatening situations solely because of the color of their skin. We can often get so caught up in our work and daily routines that it can be hard to remember we are all human beings. We each have our families, relationships, aspirations, joys and sorrows that shape our individual worlds—even if we live in different neighborhoods. Having concern for our fellow human beings is vital, and we must realize that not everyone experiences the same level of safety and security in the world. We may not be able to change all these things, but at a minimum, let us do our best to address that which is right in our midst.

Racism in the Workplace

Racism is brought to the forefront in extreme cases like recorded police brutality, but it is also prevalent in the office environment. In 2018, C+R Research, a market research firm based in Chicago, shared the results of a study it had conducted on diversity and inclusion in the actuarial profession. One of many pertinent facts the firm shared is that “discrimination in the [actuarial] field is real even if it is non-intentional.” (Source: “Diversity & Inclusion Research Initiative.” Presented to The Actuarial Foundation, CAS, IABA and SOA by Culturebeat—the multicultural division of C+R Research, 2018)

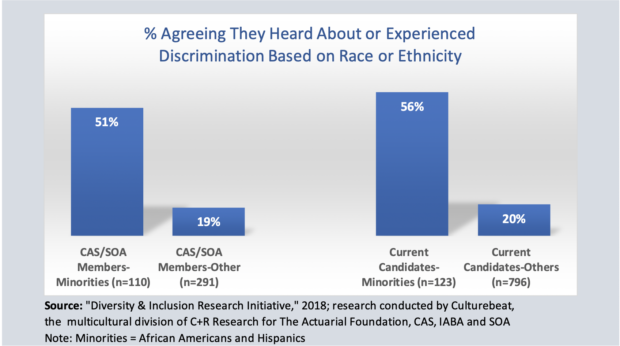

The accompanying chart also highlights the importance of listening to your minority colleagues and the challenges of spreading awareness. The study found that non-minorities in the actuarial community were less than half as likely to acknowledge racism compared to minorities.

So, what does racism in the workplace look like?

Most times it’s not overt, where Black people are openly called the “n” word in the cafeteria or where the hiring manager tells HR to “not consider anyone Black” for the position.

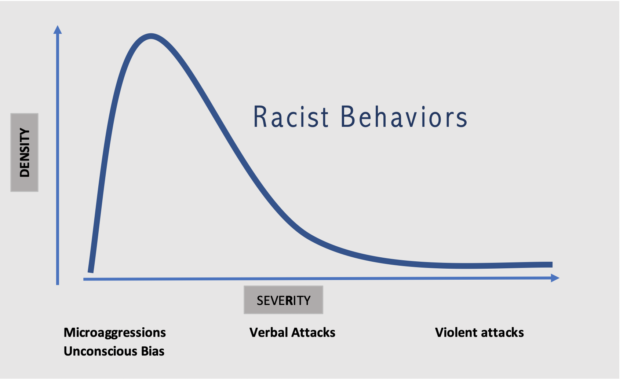

Kuda Chibanda, FCAS and member of the CAS board of directors, said it best during “Racism in the Actuarial Profession,” a session at the 2020 IABA Annual Meeting. She explained that most people think racism is all or nothing; either you’re a nice person who’s not at all racist or you are an evil person who is completely racist, akin to a Bernoulli distribution, which can only be discretely 0 or 1. But racist behaviors are actually more like a Gamma distribution (accompanying picture). There is a range of behaviors from the minor to the extreme, and it should be acknowledged that each person falls somewhere along that spectrum. You can be a very nice person and still perform lower severity racist acts, or microaggressions.

Psychologist and former Spelman College President Beverly Daniel Tatum describes microaggressions as brief and commonplace verbal, behavioral or environmental indignities. Examples include often being interrupted and talked over in meetings; making comments such as, “Wow, you speak so well” or “You don’t sound Black”; sighing loudly or yawning when a Black colleague begins a presentation; or not inviting your Black colleague to team socials.

On their website, the University of California San Francisco’s Office of Diversity and Outreach defines unconscious biases as social stereotypes about certain groups of people that individuals form outside of their own conscious awareness. Examples include mistaking a Black person you meet for the first time for an office assistant, when they are actually an actuary; spending more time checking for errors in work submitted by a Black colleague; not considering when hiring the added challenges most Black people face in pursuing this career; showing low interest in resumes with names that “sound Black”; investing less time training a Black hire; and requiring extra demonstrations of aptitude from Black men and women before promoting them.

Dr. Valerie Purdie-Greenaway, a psychology professor at Columbia University, spoke to these lower severity examples of racism in the session “George Floyd and beyond: What does real anti-racism look like in organizations and how to lead through change,” which was part of the 2020 IABA Annual Meeting. She also discussed the psychological cost to Black employees of working in such an environment. They are consistent with items LaFawn Davis, the VP for Diversity, Inclusion & Belonging at Indeed, shared in episode 12 of Indeed’s online series “Here to Help.” When someone is constantly trying their best to do the right thing at work but ends up with adverse outcomes over and over again, they can feel a lack of belonging based on their identity as a Black person. Their daily motivation weakens, leading to undermined performance as creativity, morale and engagement drop substantially while the potential for other mental health issues such as anxiety and depression rises.

These different acts of racism and the cost put on Black employees are significant contributors to the lack of representation of Black actuaries in our profession. While in the U.S. Black people make up around 13 percent of the population (U.S. Census, as of July 1, 2019), approximately 1 percent of U.S. actuaries are Black. In the future, the IABA will share the corresponding figures for Canada.

Related article, “Actuary to Actuary: How to Help Combat Racism in the Workplace“

Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  Five AI Trends Reshaping Insurance in 2026

Five AI Trends Reshaping Insurance in 2026  Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid  Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs