Many carrier CIOs face the challenge of communicating with their organization’s board of directors. It can be difficult sometimes for CIOs to know just how much communication is enough. It can also be difficult for CIOs to gauge just what their boards want to hear, and how often they want to hear it.

Executive Summary

If boards aren’t comfortable with the quantity and quality of information they’re getting from their IT leadership, then they’re less likely to approve and embrace strategic IT investments, notes X by 2’s Frank Petersmark. In this article, Petersmark speaks from his personal experience as the CIO in an effort to help insurance IT leaders overcome the challenges of CIO-board communications.In my early days as a CIO at a regional carrier, I made the mistake of communicating at too technical a level to the board, and as a result I had an uncomfortable but ultimately valuable conversation with the chairman. He told me something that still sticks with me. His very simple advice was to remember that I was the expert on what I was discussing and the board was not, and that they had confidence that I knew what I was talking about. So just give it to them in lay terms in the most concise way possible, he advised.

He also told me that what the board really wanted to hear was not about all the things that were going well but rather about those things that weren’t going well and the kinds of risks that might pose to the company.

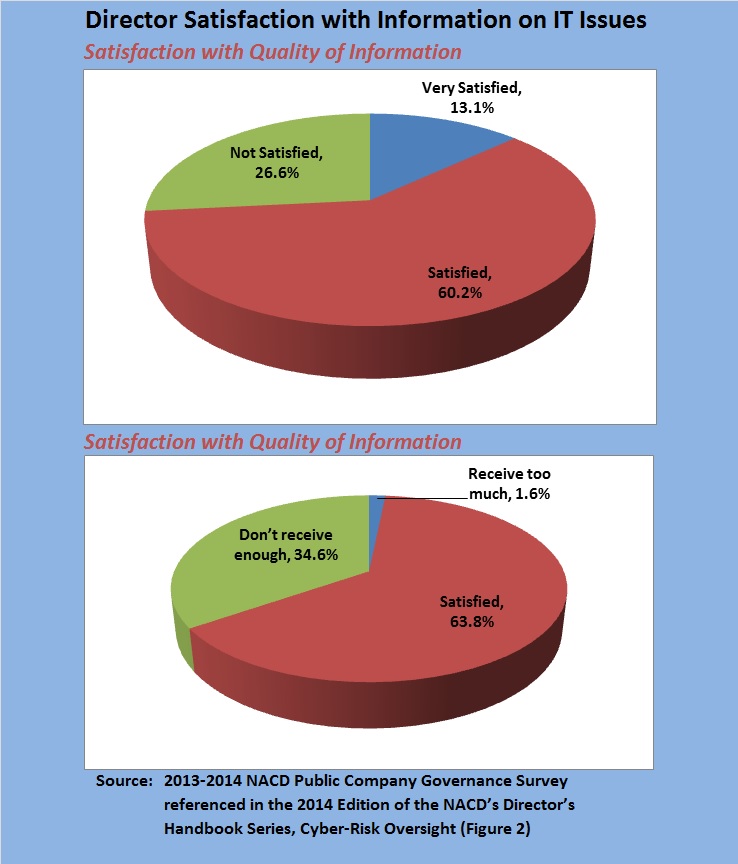

I was reminded of all of this by a recent survey conducted by the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD), in which they noted that 63 percent of the respondents across a variety of industries including financial services indicated that they had a below-average knowledge of IT-related risks in their organizations (as reported by CIO.com, “Corporate Boards Are Hungry for IT Info From CIOs,” March 28, 2014). A meager 13 percent of all the directors surveyed were “very satisfied” with quality and clarity of information they get about their organization’s IT function. That was by far the lowest score for any given topic in the survey, which also included more traditional board reporting functions like corporate performance and financial risk.

This begs an obvious question: In an era when the ubiquitous spread and use of technology and the process change it engenders are widely acknowledged as the critical factor for the long-term performance and success of every insurer, why aren’t CIOs doing a better job of communicating with their boards? And conversely, why aren’t carrier boards demanding better and more targeted IT-related information from their CIOs?

These are important questions that need to be answered. Look at it this way: If boards aren’t comfortable with the quantity and quality of information they’re getting from their IT leadership, they’re less likely to approve and otherwise embrace strategic IT investments and initiatives.

Such behaviors may have serious ramifications for any company, and the shame of it is that this is an issue that’s imminently, if not quite easily, correctable. Why? Because at its core this is a communication issue rather than a strategy or financial issue. It may well turn into a strategy or financial issue, but only after the ground rules for effective communications between the CIO and the board have been established. And whether it seems fair or not, it’s incumbent on the CIO to get this right.

So, how do CIOs get this right?

First, be cognizant of the fact that the language boards speak is the language of business. Effective communications with boards starts and finishes with couching everything in terms of business benefits, options, investments and risks. Your board of directors is much less interested in the technological machinations of the “cloud” or “big data,” and much more interested in their potential benefits to the company. That means CIOs have to do the translation for their boards and come to the table with a business-centric view of the proposed investments and initiatives.

Second, and as importantly, it’s a mistake to think boards are only interested in hearing rosy reports about those opaque IT initiatives that seem to go on forever. In fact, they are much more interested in hearing about any problems or impediments, as difficult as it might be for a CIO to share such things with them.

For example, I was once involved in an IT strategy that included an outsourcing approach as part of a larger IT strategy to modernize core systems. The outsourcing was intended to allow the incumbent IT department to focus on the new development—in collaboration with an outside vendor—while the outsourcer maintained the day-to-day IT status quo. For a variety of reasons, however, it became apparent that the outsourcing deal would have to be terminated well before its contract expiration date.

I took this issue to the board before it had gotten too out of hand, and rather than fielding questions about what went wrong and why, the conversation was more about the way the board could assist in the contract negation process. In the end, an early termination of the contract was negotiated, and while it was not easy, having the board’s support and assistance from an early stage helped to lessen the pain of the situation.

This is also where the CIO/CEO relationship comes into play. CEOs don’t like to be surprised any more than do boards of directors, so it is critical that the CIO discusses any issues he or she might be disclosing to the board with the CEO ahead of time. Assuming the CIO/CEO relationship is a strong one, the CEO can play the invaluable role of providing executive support in the board setting. Similarly, if there is an executive or board committee that oversees strategic IT initiatives and investments, it is imperative to get them on board prior to going to the full board.

In a perfect world, board members are resources to be leveraged for their experiences and perspectives, and they actually want nothing more than the opportunity to bring those capabilities to bear for the company on whose board they sit. My own experiences taught me that board members can be powerful allies, and that the time invested in some upfront education and discussion—the meetings before the meeting—goes a long way in the support or approval of some major initiative or contentious issue.

An example of this from my own experience involved a new IT strategy for the company. The strategy was a little unorthodox, as part of it involved making an investment in a software development company as a way to create a custom written commercial lines policy administration system. Before discussing the strategy with the full board, I—along with the then CEO of the company—visited several of the board members whose support for the strategy would be crucial. We explained all the reasons, implications and estimated costs for the strategy and were therefore able to address their questions prior to the next board meeting.

The time invested in doing that paid off handsomely, as the strategy was approved without incident at the next full board meeting.

Effective board members are there to ask tough questions and to provide alternative perspectives, and it is important for CIOs to keep in mind that most board members do not have strong IT backgrounds. That makes these kinds of upfront meetings, discussions and educational sessions a critical part of a CIO’s relationship to their boards, and vice versa. Increasingly, boards will begin to be comprised of former CIOs, but until then the CIO must do his or her part in clearly communicating the technology challenges and opportunities in business terms.

Finally, and back to the survey results previously noted, boards always want to know the business risks involved in any technology strategy or initiative. If you think about the board’s role with any other major functional area of the company, its primary role and value to the company is through assessing and managing business risk—e.g., asset allocation and investment performance, product mix and profitability, and regulatory and legal compliance to name just a few examples.

It’s no different, or at least it should be no different, with technology. Any business technology strategy or initiative poses an inherent risk to the company. It may be risks associated with investments, expenses, competitive advantage or even the risk of not doing something. Most boards are very good at digesting, assessing and judging risks and often have viable strategies for mitigating them.

It’s what boards do—at least the good ones—and as it turns out, it’s what they want from their CIOs.

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll  Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford  AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage