In November of last year, Allstate paused writing new homeowners policies in California. State Farm, the state’s largest homeowners writer, stopped accepting new applications for insurance back in May. Such decisions could not have been made lightly: California is the third-largest homeowners insurance market in the country, and State Farm and Allstate combined for over 25 percent of the homeowners direct written premium in the state in 2022 (based on 2022 direct written premium for homeowners multi-peril from Statutory Pg. 14).

Executive Summary

In September, the California Department of Insurance announced a set of reforms called the Sustainable Insurance Strategy to support the California property market, citing a plan to engage in public meetings to explore incorporating California-only reinsurance costs into rate filings among the reforms.Here, consulting actuaries Rob Zolla and Aaron Koch responded to a request from Carrier Management with an article that sets the stage for anticipated discussions by reviewing the impacts of California’s prohibition of reinsurance costs from both a theoretical and practical perspective.

Some of the challenges facing the California market come from deteriorating loss experience in the state, as rapid growth of housing units in the Wildland-Urban Interface and the impacts of wildfires and other disasters have led to greater insurance payouts than in recent years. However, insurers have also faced challenges due to the California regulatory approach toward approving insurance rates. Unlike many other states, the California Department of Insurance (CDI) forbids the inclusion of reinsurance costs in a company’s calculation of how much premium it needs to charge customers for most lines of business. (California Code of Regulations. Title 10. § 2644.25. Reinsurance). As the costs of natural disasters have continued to climb, this admittedly technical restriction on the premium calculation has made it more difficult for insurers to receive approval for needed rate increases, and thus operate successfully in the market.

On September 21, the CDI announced a set of reforms called the Sustainable Insurance Strategy to support the California property market. Among the reforms was a plan to engage in public meetings to explore incorporating California-only reinsurance costs into rate filings. This article sets the stage for these anticipated discussions by reviewing the impacts of California’s prohibition of reinsurance costs from both a theoretical and practical perspective.

Meeting Capital Adequacy Needs: Direct Capital Versus Reinsurance

The basic product an insurance company or residual market entity sells is a future promise to pay (if you have a claim). Thus, the biggest risk property insurers face is the uncertainty associated with the timing and amounts of future loss payments. To protect against this uncertainty, companies need to hold capital to support the payments for these potential losses. (Note: Throughout this article, the terms capital and surplus may be used interchangeably based on the source referenced.)

“The actuary should recognize that the capital which is needed to support any risk transfer has an opportunity cost regardless of the source of capital or the structure of the insurer.”

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) developed the risk-based capital (RBC) system in the 1990s “to help regulators identify insurers that are in financial trouble” and to compute a “minimum level of capital adequacy that a company must have to operate.” How capital is provided to a company can vary based on the operational structure of the company. For example, capital may come directly from outside sources such as shareholders. However, it is well understood that there is a cost for companies to hold and use investors’ capital, as capital providers can look to alternative investments other than insurance risks if they can receive a higher return on their investment for the same level of risk.

Actuarial Standards of Practice (ASOP) 30, Section 2.3 supports this idea by defining the cost of capital as “the rate of return that capital could be expected to earn in alternative investments of equivalent risk.” Including the cost of capital in the calculation of insurance rates is required to develop an actuarially sound rate.

However, property/casualty insurance companies and other residual market organizations can also implicitly meet their capital needs by purchasing reinsurance to transfer risk to other risk bearing entities. Purchasing reinsurance can serve many functions for a company, including allowing the company to reduce its net exposure to loss and lower its surplus requirement. (See, for example, “Reinsurance Accounting & Strategy for the Actuary” by Derek Cedar and Andrew Thompson, p. 9)

Reinsurance protection can be particularly important for entities that face the potential of severe losses from natural catastrophes, such as hurricanes or earthquakes. The loss potential posed by these types of events is so massive that it can threaten the solvency of individual insurers, making it desirable for these risks to be spread across the broader reinsurance marketplace.

The benefits of reinsurance come at a cost to the primary insurance company, as the reinsurer will expect to earn a profit from assuming this risk. To provide guidance on the matter, ASOP 29, Section 3.7 states “the actuary may elect whether to include the cost of reinsurance as an expense provision.” In recent years, including reinsurance costs in a ratemaking analysis has become commonplace as these costs have increased substantially for certain types of risk. (See, for example, “Basic Ratemaking” by Geoff Werner and Claudine Modlin, p. 137)

In a sense, these reinsurance costs are analogous to, and a substitute for, the cost of capital charge. If a company decides not to purchase reinsurance, it retains more risk and should expect its capital requirements to be higher than if it purchases reinsurance coverage. It therefore incurs a higher overall cost to support that capital.

The actuarial principles support this comparison, as ASOP 30, Section 3.2 states that “the actuary should recognize that the capital which is needed to support any risk transfer has an opportunity cost regardless of the source of capital or the structure of the insurer.” In addition, ASOP 30, Section 3.1 states that “property/casualty insurance rates should provide for all expected costs, including an appropriate cost of capital associated with the specific risk transfer.” Thus, whether a risk is retained on the balance sheet or ceded to reinsurers, the rate charged by an insurer should include a provision for all expected costs needed to support that risk.

Insurance Filings and the Cost of Reinsurance

State regulators do not regulate reinsurance costs directly, which can make it difficult for regulators to determine an appropriate load for reinsurance costs in ratemaking calculations. In California, except for earthquake and medical malpractice facultative reinsurance with attachments points above $1 million, the CDI has ruled that “ratemaking shall be on a direct basis, with no consideration for the cost or benefits of reinsurance” (California Code of Regulations. Title 10. § 2644.25. Reinsurance). As reinsurance costs are still borne by companies in practice, prohibiting them from being included in ratemaking calculations will prevent companies from reaching the target rate of return commensurate with the risk they assume.

This issue has recently been further exacerbated by the fact that U.S. reinsurance rates for policies that experienced claims for natural catastrophes rose 30-50 percent in 2023 from the prior year, driven by recent loss activity and a shortage of reinsurance capital. As a result of these market dynamics, it is understandable why companies such as State Farm and Allstate have recently stopped writing new homeowners insurance policies in California. The CDI itself has directly cited these increasing reinsurance costs in its response to company actions, stating in a May 30, 2023 Consumer Alert that “the factors driving State Farm’s decision are beyond our control—climate change challenges, higher reinsurance costs affecting the entire insurance industry, and global inflation.”

Excluding Reinsurance Costs: What is the Impact?

Since reinsurance costs are ultimately a substitute for direct costs of capital, we can better understand the ratemaking process in California by understanding how companies are allowed to incorporate cost of capital into their rate filing support. California Code of Regulations (CCR), Title 10, Section 2644.16–Catastrophe Adjustment provides guidance on the maximum and minimum permitted after-tax rate of return on capital as follows:

- The maximum permitted after-tax rate of return means the risk-free rate, as defined in section 2644.20(d), plus 6 percent.

- The minimum permitted after-tax rate of return shall be -6%, which the Commissioner finds is high enough to prevent any undue risk of insolvency and to prevent injury to competition through predatory pricing.

As of August 2023, the risk-free rate of return calculated by the CDI is just below 4.6 percent, resulting in a maximum permitted after-tax rate of return on capital of just under 10.6 percent. This rate is actually substantially higher now than over the past decade, due to recent increases in interest rates. By comparison, the average maximum allowable rate of return from 2012 to 2021 was 7.5 percent. (For readers interested in the details, see related sidebar, “Permitted After-Tax Returns for California Insurers (2012-2021)“)

How does this compare to the necessary returns that insurance company shareholders expect?

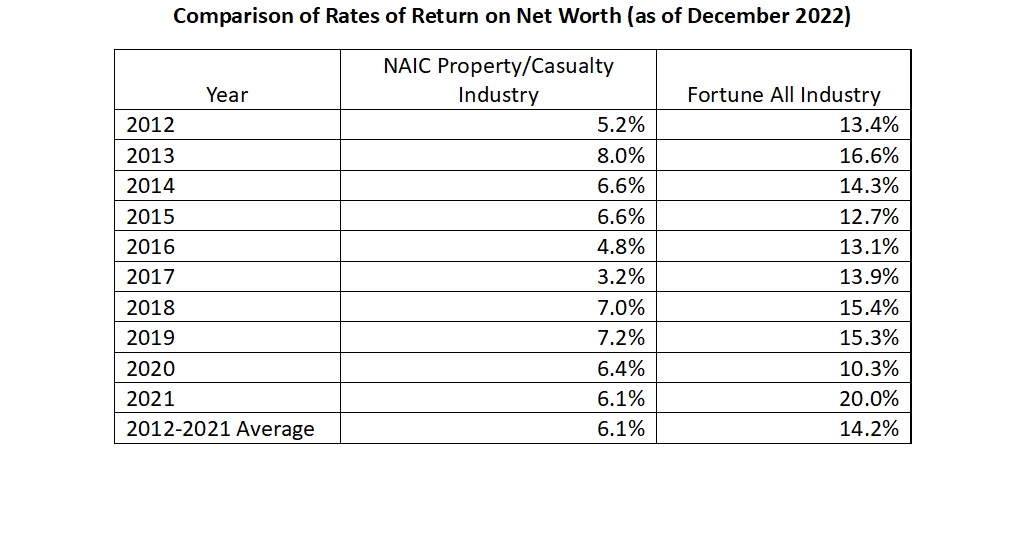

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) 2022 Report on Profitability by Line and by State provides a comparison of the rates of return on net worth for the last 10 years (through 2021) for the property/casualty insurance industry. We can compare this to Fortune magazine’s all-industry average, which represents an approximation based on a simple average of Fortune’s industry and service sectors, as shown below.

Assuming that property/casualty companies needed to target at least a 6.1 percent rate of return on net worth from 2012 to 2021, this can be translated to a 7.1 percent rate of return on surplus. (See related sidebar, “Calculating Targeted California Returns on Surplus” for the supporting calculations) This already almost exceeds the average CDI maximum allowable rate of return during this period (7.5 percent), without accounting for several factors that would require companies to seek even higher returns:

- Property risks may require a higher return on surplus than the entire P/C industry, due to the volatility of the line of business.

- The P/C industry return on surplus also accounts for the industry utilizing reinsurance to lower insurance company surplus requirements. If insurers were to no longer purchase reinsurance, this would raise the ratio of net premium to surplus and therefore increase the range of required return on surplus.

- The CDI does not allow the net cost of reinsurance to be considered in the calculation of the indicated rate level.

Pretty quickly, it becomes apparent why companies’ target returns on surplus are likely to exceed the maximum allowable return permitted in California.

What is Next for the California Property Market?

While there are a myriad of factors that have impacted the California insurance market, increased reinsurance costs and not allowing companies to charge for these costs, or a higher cost of capital necessary to support catastrophe exposed book of business, limit a company’s ability to meet its target rate of return on capital. The California insurance market has faced challenges over the past few years as companies have nonrenewed existing policies and limited or restricted the writing of new policies. Insurers initiated 241,662 nonrenewals of homeowners insurance policies in California during 2021, which was a nearly 30 percent increase from the prior year. (Source: “State Farm stops new home insurance sales in California as wildfire risks grow,” May 30,2023, Reuters citing CDI data) The number of policies in the California FAIR Plan, the state’s insurance placement facility, increased 54 percent from the middle of 2019 to the end of 2020.

“Property/casualty insurance rates should provide for all expected costs, including an appropriate cost of capital associated with the specific risk transfer.”

This combination of outcomes has helped lead to the CDI’s release of the Sustainable Insurance Strategy. Incorporating reinsurance costs in insurance rates is only one part of the Strategy, and notably there has been no explicit promise from the CDI that the public meeting process will result in a change in its position. Furthermore, allowing reinsurance costs into the ratemaking process will only matter if companies are able to get approval of the required rate increases that this actuarial process would indicate.

Nevertheless, the table has now been set to consider reinsurance costs, and the timing is good, as reinsurance has never been more important in California’s increasingly disaster-driven property market than now. Like all states, California will benefit in the long term from having a robust, competitive insurance market, and allowing reinsurance costs to be incorporated into property rate filings would be an important step to assist with the mission set out in California Insurance Code, Section 10090.(c): “to encourage maximum use, in obtaining basic property insurance, of the normal insurance market provided by admitted insurers and licensed surplus lines brokers.”

***

Read more: “Permitted After-Tax Returns for California Insurers (2012-2021)”; “Calculating Targeted California Returns on Surplus“; “A Community-Based Solution: How Actuaries and Fire Chiefs Can Tackle WUI Risk Together”

State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists

State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists  From Skill to System: The Next Chapter in Insurance Claims Negotiation

From Skill to System: The Next Chapter in Insurance Claims Negotiation  New Texas Law Requires Insurers Provide Reason for Declining or Canceling Policies

New Texas Law Requires Insurers Provide Reason for Declining or Canceling Policies  Focus on Ski Guides After Deadly California Avalanche Could Lead to Criminal Charges, Civil Suits

Focus on Ski Guides After Deadly California Avalanche Could Lead to Criminal Charges, Civil Suits