As the founder of a data and analytics InsurTech focused on the commercial auto insurance space, I knew fundraising would be a challenge.

Commercial auto insurance has been unprofitable for years, and industry executives would be naturally skeptical that my solution would make it better. As my insurance industry friends said, “You sure picked a hard problem to solve.”

Executive Summary

“Don’t let VCs be the gatekeepers of your success.” That’s one of the clearest lessons that tech entrepreneur CEO Kevin Henderson learned when he set out to raise capital for a startup that helps insurers incorporate telematics and other data into their underwriting and business processes. In this article, which he originally wrote for TechCrunch, the Black executive writes about the challenges of raising funds for an InsurTech focused on the commercial auto space and how he is succeeding in spite of them. In addition, he offers some ideas about how the insurance industry operates differently from VCs.A version of this article was previously published by TechCrunch and on Kevin Henderson’s LinkedIn page under the title, “Don’t Let VCs Be The Gatekeepers of Your Success.” Carrier Management is republishing with permission of the author and TechCrunch.

Even as a first-time founder, I did not anticipate how difficult it would be to raise venture funding, but the experience offered some insights into why so few Black entrepreneurs are funded by VCs.

The odds of winning a venture round are low for everyone, but Black founders have a better chance playing pro sports than they do landing venture investments.

About Me and Indenseo

Before I share more about my experience in trying to get VC funding and the lessons I learned, let me provide some context for this article.

I have struggled for years about whether or not to write a piece like this.

Speaking out about racism goes against every lesson I have learned since I was the only Black kid in my first-grade class in the Boston suburbs:

Save candid conversations about race for Black people.

You’re being a victim.

People will think you’re whining or making excuses. They’re not interested.

Don’t make white people feel uncomfortable.

In a professional environment, speaking up could be career suicide. But now is not the time to be silent.

The startup I founded, Indenseo, is a data and analytics software InsurTech company that provides automated underwriting services, software and analytics services to the insurance industry.

Despite strong customer relationships and support from angel investors, we didn’t complete building solutions and moving the company forward until we stopped taking unproductive pitch meetings with VCs. Some of my white colleagues who attended those meetings characterized these encounters as disrespectful and dismissive, but for me they were par for the course.

I was raised by a single mother in West Medford, Mass., and worked my way through Harvard, located about five miles away. Before starting Indenseo, I worked for @Road, a fleet management telematics company that was acquired by Trimble, a company whose goal is to transform “the way the world works by delivering products and services that connect the physical and digital worlds.” There, I led a team that pioneered the sale of telematics data, which started with using data for traffic predictions and expanded to other markets, including insurance.

At Trimble, I saw the difficulty legacy insurance carriers faced when they tried to incorporate new types of data into their underwriting and business processes. I started Indenseo to solve this problem by combining deep insurance industry experience with the nimbleness of a startup.

The Fundraising Challenge

Fundraising is hard. Relatively few startups receive VC funding. I did consider race might be a factor that could make long odds even longer. It has been a factor throughout my life whether I ignore it or not. For example, I once had a job interview and the hiring manager told me during the interview the company had never hired a Black professional and they weren’t ready to hire one. Without cataloging here every unambiguous racial incident that I’ve experienced, they have been frequent enough to know that it can happen at any time without warning.

It’s unknowable when and how much of a factor race is as I continue to develop Indenseo. So, I just forge ahead with my plans based on business fundamentals. There isn’t a “was that action, statement or decision influenced by race?” metric I can factor into a fundraising strategy or a pitch deck.

How low are the odds of winning a venture round for Black founders?

According to a Harvard study, between 1990 and 2016, just 0.4 percent of the entrepreneurs who received funding were Black. That’s 188 Black entrepreneurs versus 34,000 white entrepreneurs in total, or about seven per year.

In 2016, nine Black NFL quarterbacks started at least one game during the season. Should anyone wonder why ambitious young Black men pursue sports careers?

I got the meetings and pitched Indenseo to investors in Silicon Valley, New York City, Chicago and Boston. I expected that my experience, my best-in-class team, the compelling Indenseo proposition, market fit, and the financial and advisory backing of notable insurance executives would land the dollars, despite the odds.

I was wrong.

Trying to Beat the Odds

One recurring phenomenon we frequently encountered were dismissive and disrespectful investors (in the words of a white colleague). When I had one disappointing meeting after another, people in my multiracial network—many with extensive fundraising experience—told me it didn’t make sense. I’d resisted getting distracted by race as a factor, but white colleagues were saying that something wasn’t adding up. They said it was more than my assumption that most investors are jerks.

As Toni Morrison said, “The very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work.” My own lived experience is that it’s an added factor that Black entrepreneurs have to manage.

I followed advice given to many Black founders: Take a white colleague to your pitch meeting. I brought colleagues who had done a lot of fundraising themselves; some of these meetings were with their contacts. I tried this strategy dozens of times, and my colleagues were repeatedly shocked at the treatment we received.

But if I lose my temper, I’d likely be labeled as just another angry Black man.

I did let my frustration show once when I directed a VC’s attention to the milestones we’d met and industry support we had gathered.

“What does it take for us to get a check from you?” I asked. His response: There is nothing you can say or do to get me to invest, but if you get another VC to lead the round, call me.

In another conversation with a VC, I pointed out the lack of diversity in both the ranks of investors and the entrepreneurs they choose to fund. He replied that Silicon Valley has produced the greatest accumulation of wealth in human history in the last 25 years. Why do we need to change anything?

Then there are the grifters. I don’t think Black founders are the only ones whose ideas get stolen after pitch meetings, but it happened to me.

We pitched a VC firm that had a consultant with an insurance background on their team to help evaluate the Indenseo opportunity. VCs don’t sign NDAs, but we did sign one with the consultant, who said Black founders can’t get companies funded but white founders can. (Yes, he said it.)

He later tried to ingratiate himself by saying he was considering investing too. Instead, he founded a company that copied our ideas. (So much for our NDA.)

“I assumed most investors were jerks, but my white colleagues were shocked.”

So, why didn’t I sue him for violating the NDA? I consulted with some of our angel investors and they said we would be better off fighting them in the marketplace, given our limited time and resources. It wasn’t the first time our ideas were stolen.

When another company we pitched appropriated some of our ideas, my contact there informed his executives that they’d signed an NDA with Indenseo. Their reply: Indenseo doesn’t have the money to sue us. But they weren’t domain experts and we had left out much about our plans. They announced their launch in The Wall Street Journal, but as I expected, they failed.

Where Are Black VCs?

Am I calling VCs racists? I don’t know what’s in their hearts, but I do know what’s in their numbers.

Dealing with unconscious bias is difficult as a Black entrepreneur trying to build a company. You know it exists, and you have to figure out a way to manage around it. But it’s a subtle problem.

“There are other funding sources, such as angel investors, corporate strategic investors, crowdfunding and more. There is funding outside the United States. Don’t overlook international investors.”

I have never pitched at a VC firm that had a Black person in the room. And the pipeline excuse doesn’t work. There are Black people with technical degrees who aren’t hired at VC firms and white VC investment partners who earned liberal arts degrees.

Sure, there are funds started by Black VCs, but they encounter unconscious bias too when raising money. While more Black VCs with more capital is a crucial element of addressing underrepresentation, does that mean VC firms that aren’t founded by Black investors don’t have to change anything?

Lessons Learned

Deciding to stop the time-consuming VC pitch process and go in another direction to fund and develop the company was quite liberating. Moving forward, we’re free to manage our startup without wondering how VCs will view our decisions in the future when we seek funding.

A lesson I’ve learned from my experiences: Don’t let VCs be the gatekeepers of your success. There are other funding sources, such as angel investors, corporate strategic investors, crowdfunding and more. There is funding outside the United States. Don’t overlook international investors: There is wealth in African countries. I found a way of funding the company that works for Indenseo.

We raised money from angel investors (including the former CEO of one of the world’s leading analytics software companies and his wife). In addition to money, it expanded our knowledge and improved our products.

Another lesson learned: Angel investors may be more helpful to your company than VCs.

The ultimate judgment on Indenseo’s products and team will be rendered by customers, partners and domain experts. The insurance industry has unique metrics that determine a company’s profitability. If you’re selling analytics software and services, either your solution is helping improve those metrics or it isn’t. The insurance industry is validating our market fit and survival skills.

“I’ve never pitched at a VC firm that had a Black person in the room.”

There is a process to get insurance industry trust, and many senior executives in the industry are reluctant to invest the time in startups that’s necessary for them to get that trust. That’s because they aren’t convinced the startup will persevere to get through the process of getting that trust.

We are able to get time with those executives because they trust our team and they don’t doubt that it’s worth their time to talk to Indenseo. They know we won’t fold when times are difficult.

A change I’ve seen since I started Indenseo that works in our favor is insurers don’t rely on VCs to act as a de facto screen for which InsurTechs have the best teams and solutions. That’s because they don’t have confidence in investors’ judgments about InsurTech companies.

We’ve developed Indenseo with angel investors and sweat equity. The key to our success is the amazing team, our advisory board and using capital efficiently. They remind me that you’re not the only one with an emotional investment in this company. When I started this company, the only people in the insurance industry I knew were the people I had interacted with when I worked at Trimble.

Most of the people on our advisory board and team with insurance industry backgrounds are people I’ve met since I started Indenseo. It takes time to build those relationships. Because of them there is no corner of the commercial property/casualty insurance industry we can’t access. The head of InsurTech at a global reinsurance company told me that ours is the best-balanced team of any InsurTech company they’ve seen.

We are in the early stages of showing our flagship product, and it isn’t available for general release yet. Our VP of Engineering is telling me about a new concern: that we don’t take on too many customers too quickly.

Concluding Thoughts: What About the Insurance Industry

Most of what I have written here has been previously published in a technology publication called TechCrunch (TechCrunch article: “Don’t Let VCs Be The Gatekeepers of Your Success“). That’s fitting because my background is in technology not insurance. I’ve never worked for a company in the insurance industry.

Carrier Management, however, has asked me to add my thoughts on race in the insurance industry.

Would I have gotten further along in developing partnerships within the insurance ecosystem, including deals with carriers, if I were white?

I don’t know. As I wrote in my TechCrunch article, I don’t think companies and investors make conscious decisions to not invest in or do business with companies led by Black founders.

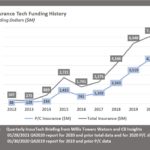

I can’t offer any direct insights about insurance carriers and race based on my direct experiences. I haven’t spent a career in this industry and I’m not close enough to the inner workings of carriers and reinsurers to offer an accurate view. For the most part, as I meet with carrier executives, they have focused on what Indenseo can offer to increase their profit potential. We’re getting their attention and gaining momentum. But I don’t know if younger, white male Silicon Valley founders, whose advisory boards and teams don’t have the domain expertise of Indenseo, are having an easier time. (Article continues below.)

This moment presents a great opportunity for the insurance industry. Silicon Valley companies and VCs have well-documented challenges with recruiting and retaining diverse candidates. In a battle for talent, if the insurance industry can prove itself to be a more welcoming industry for diverse candidates—where companies do more than talk a good game—it will give them a leg up in the battle for talent. This could be a difference maker as the industry needs to recruit young talent to replace the boomers as they retire. It’s also good for business. A number of studies in the last five years have shown that diverse teams get better financial results. (“Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter,” in Harvard Business Review, summarizes several of them.)

I grew up in the Boston area during a period when getting called the N-word was almost a daily occurrence, so to survive you start to become desensitized to this issue. It is possible that the same lifelong lessons, which almost held me back from writing about my experiences in the first place, may be preventing me from attaching bias labels to insurer actions that have been less overt than those of the VCs I have encountered. But I haven’t focused on race in my dealings with the industry. That would be a distraction from my goals of building a great team and a great product and presenting our capabilities to insurers.

There is a lot of change happening in the industry. Carriers’ business will look different in 10 years—but what will their workforce look like in 10 years?

10 Do’s and Don’ts of a Smart ORSA Report

10 Do’s and Don’ts of a Smart ORSA Report  State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists

State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists  Premium Slowdown, Inflation Factors to Lead to Higher P/C Combined Ratio: AM Best

Premium Slowdown, Inflation Factors to Lead to Higher P/C Combined Ratio: AM Best  High Court Ruling on Trump Tariffs to ‘Ease Uncertainty,’ Says AM Best

High Court Ruling on Trump Tariffs to ‘Ease Uncertainty,’ Says AM Best