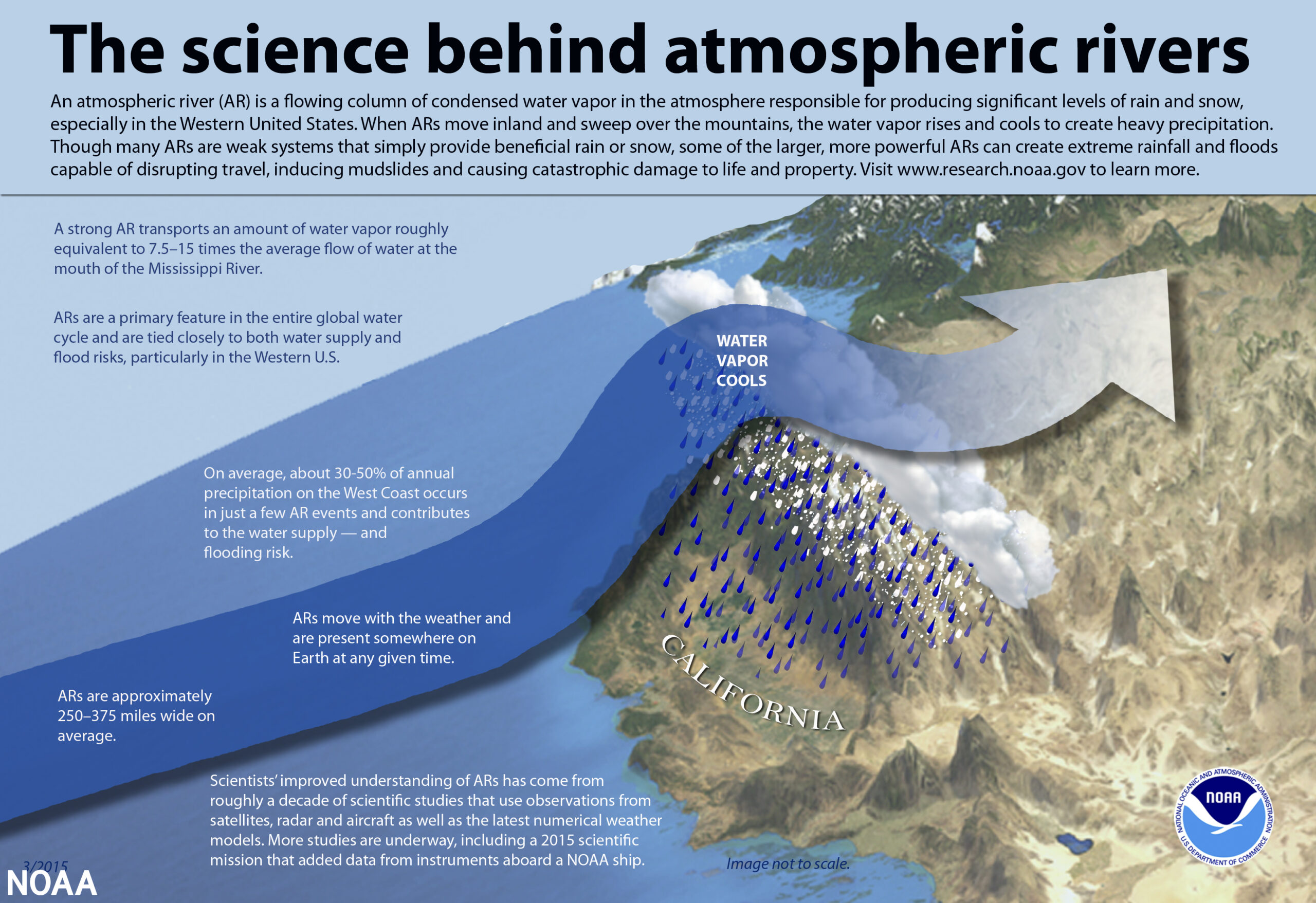

The heavy precipitation seen earlier this year in California highlighted a meteorological event known as an atmospheric river (AR) — described as long, narrow corridors of water vapor that with the required rising of air or lift can cause heavy rains and snow — leading to possible flooding and damage.

The severe storms between December 2022 and March 2023 demonstrate the impact of ARs “that drive much of California’s climate, especially throughout the fall and winter months,” according to a new Karen Clark & Company (KCC) white paper, “From Drought to Deluge The Implications of California’s Atmospheric Rivers.”

“As moist air rises, the air cools and the moisture condenses, bringing rain or snowfall,” stated the KCC white paper.

According to the report, 90 percent of Earth’s North/South water vapors are carried via atmospheric rivers.

An AR severity scale, much like the Saffir-Simpson scale for hurricanes, measures severity by accounting for both the physical characteristics and the potential destruction of ARs.

Because of California’s location on the Pacific Coast, the state is predisposed to frequent ARs.

The lift for precipitation in California comes from two mechanisms, according to KBB, mountain ranges and ETCs (extratropical cyclones).

In the white paper, KCC explains that “landfall in the context of an AR refers to the location on the coast where the highest concentrations of water vapor within the corridor of moisture encounter land.”

ARs lack a well-defined center or eye, unlike hurricanes or tropical storms, making the definition of “landfall” less rigid.

Each year, the number of AR events in California that make landfall fluctuates.

On average, 14 ARs, mostly Category 1 and 2, make landfall each water year—the 12-month period from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30.

According to KCC analysis, the 2022-2023 water year was above average with 18 AR events.

ARs typically occur in late fall, winter and early spring months when the low temperatures at high latitudes mean the precipitation falls as snow.

In recent years, there has been more precipitation but less snowpack, a potential twofold consequence of climate change, stated the report.

According to the KCC white paper, a number of intense ETCs occurring in quick succession enhanced the precipitation coming from ARs during the 2022-2023 water year.

This led to a lot of rainfall occurring over short periods of time, which then led to extreme flooding, in part, due to reservoirs that quickly filled, the report added.

“The flooding was exacerbated by the rapid sequence of storms that prevented full watershed recovery between each event. Prior precipitation decreased the land’s capacity to absorb additional moisture, raising the risks of flooding and landslides,” the report stated.

Roofs collapsed because snow from one AR event absorbed rain from another, increasing the weight of the snow.

Strong winds were also a factor that compounded the damage from flooding and snow, the KCC report added.

Notwithstanding the damage caused by frequent rain and snowfall, the excess precipitation also leads to the growth of more wildfire fuel.

Though there are similarities between the 2016-2017 winter season and the 2022-2023 winter season, KCC said insurers shouldn’t automatically expect a severe fire season in 2023 like the one that occurred in 2017.

However, the extent of how a fire season plays out is based on a variety of factors, including temperature and weather systems.

While La Niña tends to correspond to drier conditions, like in 2017, El Niño tends to correspond to wetter conditions, as is forecast for 2023, the report noted.

With El Niño conditions tending to lower the risk of fire activity in California, 2023’s fire season is unlikely to resemble California’s 2017 fire season.

Study: AI May Be Tempering Insurer Hiring

Study: AI May Be Tempering Insurer Hiring  More Paid Time Off Keeps U.S. Workers From Quitting: Study

More Paid Time Off Keeps U.S. Workers From Quitting: Study  State Farm’s California Homeowners Rate Request: It’s Settled — Almost

State Farm’s California Homeowners Rate Request: It’s Settled — Almost  How State Farm, USAA Boost Customer Retention: Historic Dividends

How State Farm, USAA Boost Customer Retention: Historic Dividends