While conventional wisdom suggests the bigger the vehicle the safer, new research from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety shows that’s not necessarily true.

IIHS has been studying crash compatibility — how the interaction between different vehicles affects the relative safety of their occupants — for many years.

In the latest update, researchers examined two-vehicle crashes that occurred between 1- to 4-year-old cars, SUVs and pickups. They looked at two periods, 2011-16 and 2017-22, and calculated driver death rates for vehicles and their crash partners per million registered vehicle years (i.e., one vehicle registered for one year).

“For American drivers, the conventional wisdom is that if bigger is safer, even bigger must be safer still,” IIHS President David Harkey said. “These results show that isn’t true today. Not for people in other cars. And — this is important — not for the occupants of the large vehicles themselves.”

In general, the researchers found that compatibility across vehicle types has continued to improve, a phenomenon that IIHS first documented in 2011 and analyzed most recently in 2019.

For years, SUVs and pickups posed an outsize threat to people in cars, in part because their force-absorbing structures were not aligned, according to the safety institute. So when an SUV or pickup struck a car, it bypassed the car’s crumple zone and rode up over the hood of the smaller vehicle.

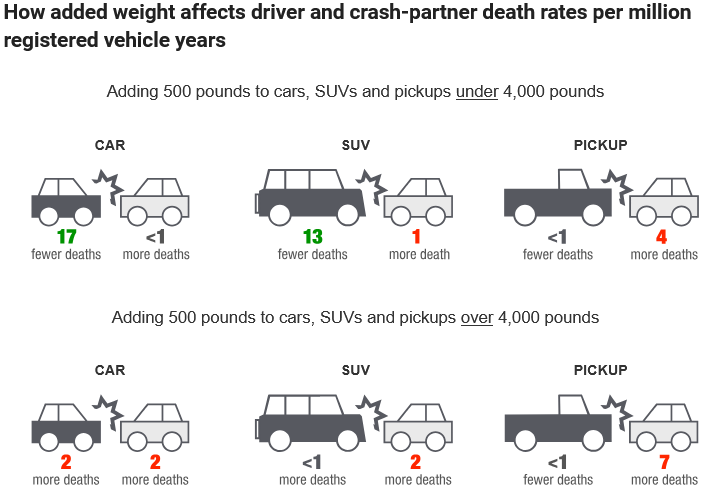

For vehicles that weigh less than the fleet average, the risk that occupants will be killed in a crash decreases substantially for every 500 pounds of additional weight. But the benefits top out quickly. For vehicles that weigh more than the fleet average, there’s hardly any decrease in risk for occupants associated with additional poundage.

On the flip side, adding 500 pounds to a lighter-than-average vehicle poses virtually no increased risk to people in other vehicles. But the same weight increase for a heavier-than-average vehicle increases the danger to people in other vehicles, data showed.

Beginning in 2009, automakers modified the front ends of their SUVs and pickups so they would align better with cars’ energy-absorbing structures. They also strengthened the structures of their cars and added side airbags to all varieties of vehicles to protect occupants in T-bone crashes, the IIHS said.

As a result, both SUVs and pickups became substantially less dangerous to people in cars than they were earlier.

Because the study looked at 1- to 4-year-old vehicles, some SUVs and pickups in the 2011-16 sample dated from before automakers changed the structure of their front ends. In those years, car occupants were 90 percent more likely to die in crashes with SUVs weighing more than 5,000 pounds as in crashes with other cars. (SUVs of that weight include most vehicles classified as large SUVs in the IIHS rating system.)

In contrast, between 2017 and 2022, those heavy SUVs were only 20 percent more likely than cars to result in car-partner fatalities.

Compatibility improved almost as much for pickups, though they remained dangerous to drivers in cars.

Pickups were 2½ times as likely as cars to result in car-partner fatalities in 2011-16 but a little less than twice as likely in 2017-22.

Now that their force-absorbing structures are better aligned with those of cars, a greater share of the risk they pose to crash partners comes from their weight, according to researchers.

The average weight of passenger vehicles in the study sample was 4,000 pounds.

For cars below that average, every additional 500 pounds in curb weight reduced the driver death rate by 17 deaths per million registered vehicle years, while only increasing the death rate for crash-partner cars by one.

In contrast, for pickups above the average weight, every additional 500 pounds only reduced the driver death rate by one but increased the death rate for crash-partner cars by seven.

“There’s nothing magical about 4,000 pounds except that it’s the average weight,” said Sam Monfort, a senior statistician at IIHS and lead author of the study. “Vehicles that are heavier than average are more likely to crash into vehicles lighter than themselves, while the reverse is true for vehicles that are lighter than average. What this analysis shows is that choosing an extra-heavy vehicle doesn’t make you any safer, but it makes you a bigger danger to other people.”

Changes in vehicle weights account for some of the improvements in compatibility as well as the continued gap between SUVs and pickups.

The weight of the average U.S. car increased to 3,308 pounds in 2017-22 from 3,277 pounds in the earlier period, bringing the category closer to the 4,000-pound all-vehicle average.

As that was happening, the portion of SUVs weighing more than 5,000 pounds fell from nearly 11 percent of all late-model SUVs in 2011-16 to 7.4 percent in 2017-22.

In contrast, pickups got larger. The proportion weighing more than 4,000 pounds increased to 97 percent of late-model pickups in 2017-22 from 91 percent in the earlier period.

“It’s a positive development that cars and SUVs are now closer in weight,” Harkey said. “These numbers show that transitioning to lighter pickups could have big benefits too, especially since many drivers don’t use their trucks for carrying heavy payloads.

Telematics and Trust: How Usage-Based Insurance Is Transforming Auto Coverage

Telematics and Trust: How Usage-Based Insurance Is Transforming Auto Coverage  The Future of HR Is AI

The Future of HR Is AI  From Skill to System: The Next Chapter in Insurance Claims Negotiation

From Skill to System: The Next Chapter in Insurance Claims Negotiation  State Farm Mutual to Pay $5B Dividend to Auto Insurance Customers

State Farm Mutual to Pay $5B Dividend to Auto Insurance Customers