Labor-intensive and time-consuming, that’s how research connected to litigated claims files is often described.

Time is a commodity, and if a case requires researching applicable laws, venues, judges and jury awards, the cost can be exorbitant. But analytics may prove to be the tipping point, offering research results in a matter of minutes.

Executive Summary

Learning that an insurance case before a particular judge will take over two years to get to summary judgment is a valuable insight that carriers can uncover from a legal analytics platform, helping the carrier with the ultimate litigation question: Do we fight or do we settle? According to Lex Machina executive Owen Byrd, the platform also delivers insights into a carrier’s own case handling, information about law firm successes to vet new firm appointments and competitive intelligence about how the insurer stacks up against other carriers.According to Owen Byrd, Lex Machina’s general counsel and chief evangelist, “Legal analytics is very different from traditional legal research.”

He explained that legal analytics takes the underlying raw information from cases, including docket entries, documents, briefs and opinions, and creates data-driven insights into the behaviors of organizations and people in the litigation ecosystem.

Byrd likened the concept to analysis used to assist professional baseball teams highlighted by the book and subsequent movie “Moneyball.”

“Sports has been transformed with analytics. You still need coaches who understand the game and have lots of wisdom and experience, but they now supplement that with statistics and data-driven insight,” he said.

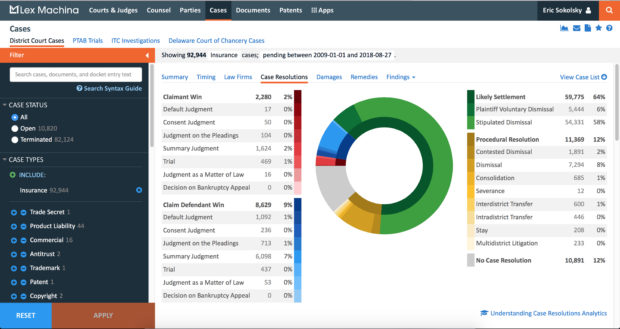

LexisNexis’ acquisition of the Silicon Valley tech company Lex Machina more than two years ago offered greater access to legal content that allowed the firm to roll out the litigation analytics product to the insurance industry. The data available is derived from 92,000 pending federal cases open between 2009 and today.

“Most of these cases arise or are heard under state law, but because the two parties are in different states—that’s called diversity jurisdiction—they end up in federal court,” said Byrd. “In most of these cases, the federal court is applying state law but the case is tried in federal court.”

Cases are complex and typically involve a policy dispute between an insurer and either the policyholder or a third party or another insurer that may be asserting the rights of a policyholder.

“These cases involve a policyholder enforcing the right to be defended against third-party liability, a policyholder enforcing payment under a claim, or it could be a declaratory judgment of rights under the policy or a claim between two insurers,” he explained.

Four specific case tags—business liability, homeowners policy, auto and life—were created to assist in quick searches.

“Insurance policies are technical documents, and the judicial rulings are often pretty dense,” said Byrd. “We added a lot of specific coding about findings that a court makes, specific remedies that are applied or specific damage types. We also added tags for hurricane-related cases and for uninsured/underinsured motorists’ cases.”

The case tags are particularly useful, he said.

“It’s important, sometimes, to be able to exclude a particular case type,” Byrd explained. “Let’s say I have a case that is not hurricane-related and I can exclude hurricane cases. That’s going to give me better insights into what happened in these insurance cases, excluding hurricane.”

The web-based platform doesn’t include interpleader motions and claims involving surety bonds, non-insurance subrogation, Medicare, Supplemental Security Income and ERISA.

The platform provides information about judges, lawyers, parties, behavior and litigation.

The platform enables a party and its lawyers to gain insight into how a judge may likely behave or how other insurers deal with a certain type of case, Byrd stressed. Insurers can even gain big-picture insights into their own case handling.

An insurer can see its average time to get summary judgments on cases and evaluate specific factors, such as the average time to summary judgment in a particular jurisdiction. The platform uncovers important details to help determine how long a case will be open and how much it might cost, he said.

Law firms most frequently used by an insurer can be identified and evaluated on case disposition.

Another available insight is “whether the claimant or the defendant wins and at what stage of the proceeding,” said Byrd.

Insurers can run searches to determine the number of cases an insurer had with a finding of bad faith and the damages awarded. Insurers can even drill down to damages awarded in cases it is a party in.

An insurer is able to look to see how courts have handled similar cases and what kinds of damage awards have been awarded, said Byrd, who added that the data aids insurers in evaluating their exposure.

Outlining additional information that can be gleaned from the platform by example, he said, “We know every time in the last 10 years where a case has had a finding, whether there was a duty to defend, a duty to indemnify, or duty to indemnify or pay some other breach of contract. Those are the three key findings.”

The rest of the findings provide the reason or the explanation for the rulings around why the insurer had or did not have to pay, explained Byrd.

Consider, for example, an insurance company involved in a federal insurance case that wants to establish that there was no proof of loss by the insured. “This is the first time you [the insurer] can go to all those cases where there was a finding of no proof of loss,” he said. “You can see exactly which stage of the case that finding was made.”

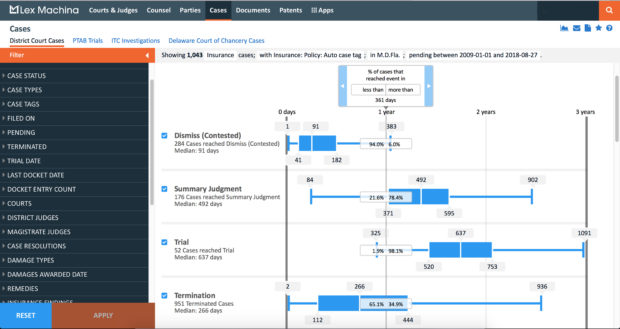

The details provided by the data can be extremely helpful to claims handlers and counsel. Byrd offered an example where an insurer researches a judge to determine the length of time for a summary judgment motion to be decided.

“Let’s say you’re in front of this particular judge in the middle district of Louisiana and you want to…look just at his insurance cases and see how long it is going to take. In front of this judge, an insurance case is going to take 658 days just to get the summary judgment, let alone trial,” said Byrd. “That’s a really valuable insight that can inform ‘Do we fight or do we settle?'”

An insurer can see which law firm has the most experience representing defendants in insurance cases in front of that judge.

“There’s huge competitive intelligence that is available through looking at the data in a comparative way between two insurance companies or a couple of different law firms or judges.”

“There’s huge competitive intelligence that is available through looking at the data in a comparative way between two insurance companies or a couple of different law firms or judges.”“You can see all the other insurance companies he has represented and what kind of outcomes he has obtained for those other clients,” said Byrd.

Competitive Intelligence

Additional tools allow comparison of a variety of litigation behavior, such as between two parties and among judges. Byrd cited the example of a side-by-side insurer comparison to evaluate differences in their approach to federal litigation.

“I’m able to run this report and look at everything from the damages that they’ve endured versus what we’ve endured, how long it takes these cases to go through the system, the rates at which they settle and we settle, and which districts and judges are we most familiar with versus what they’re most familiar with,” he said. “There’s huge competitive intelligence that is available through looking at the data in a comparative way between two [insurance] companies or a couple of different law firms or judges.”

Besides using the data to choose a lawyer or in deciding when to settle a case, it can also help inform underwriting decisions.

Byrd sees panel counsel, outside defense and coverage counsel, and claims department personnel accessing the platform. Subscriptions are sold to both law firms and corporate legal departments. Pricing varies based on the number of users and the size of the group.

“It more than pays for itself in one case,” said Byrd, who added that the data can help insurers successfully defend a lawsuit they may not have otherwise won. “This is the platform for gaining data-driven insights that supplement legal research to increase the odds of winning the case.”

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford  What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market  Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid