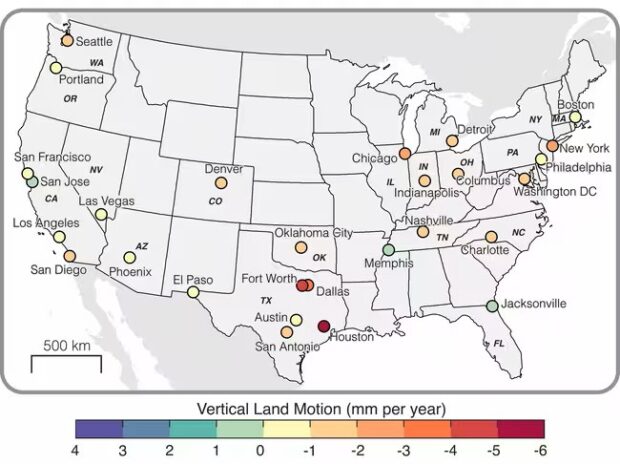

A new study of the 28 largest U.S. cities finds that all are sinking to one degree or another, whether landlocked or located on a coast.

The study, published this week in the journal Nature Cities, finds that some cities are sinking at different rates in different spots or sinking in some places and rising in others, potentially introducing stresses that could affect buildings and other infrastructure.

Massive ongoing groundwater extraction is the most common cause of these land movements, though other forces are at work in some places, according to the study’s authors.

“As cities continue to grow, we will see more cities expand into subsiding regions,” said lead author Leonard Ohenhen, a postdoctoral researcher at the Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “Over time, this subsidence can produce stresses on infrastructure that will go past their safety limit.”

Rapidly subsiding coastal metropolises such as Jakarta, Venice and New Orleans have already drawn major attention, and multiple recent studies have shown that many places along the U.S. East Coast and elsewhere are subsiding. But most studies have relied on relatively sparse data spread over wide areas to paint a broad picture, the researchers said.

Looking at all U.S. cities with populations exceeding 600,000, the new study uses recent satellite data to map out vertical land movements down to the millimeter in grids measuring just 28 meters (about 90 feet) square.

The authors found that in 25 of the 28 cities, two-thirds or more of their area is sinking. Overall, about 34 million people live in affected areas.

Houston is sinking the fastest, with more than 40 percent of its area subsiding more than 5 millimeters (about 1/5 inch) per year, and 12 percent sinking at twice that rate. Some localized spots are going down as much as 5 centimeters (2 inches) per year.

Two other Texas cities, Fort Worth and Dallas, are not far behind.

Some localized fast-sinking zones in other places include areas around New York’s LaGuardia Airport, and parts of Las Vegas, Washington, D.C. and San Francisco.

In addition to measuring surface-elevation changes, the researchers analyzed county-level groundwater withdrawals for the affected areas. Correlating this with land movements, they determined that groundwater removal for human use was the cause for 80 percent of overall sinkage.

This happens as water is withdrawn from aquifers made up of fine-grained sediments; unless the aquifer is replenished, the pore spaces formerly occupied by water can eventually collapse, leading to compaction below, and sinkage at the surface, the researchers explained. In Texas, the problem is exacerbated by pumping of oil and gas.

Continued population growth and water usage combined with climate-induced droughts in some areas will likely worsen subsidence in the future, they added.

Natural forces are at work in some areas. In particular, the weight of the towering ice sheet that occupied much of interior North America until about 20,000 years ago made the land along its edges bulge upward. Some of the bulges continue to subside at rates of 1 to 3 millimeters each year. Affected cities include New York, Indianapolis, Nashville, Philadelphia, Denver, Chicago and Portland.

Past studies have shown that the sheer weight of buildings may take a toll.

One 2023 study found that New York’s more than 1 million buildings are pressing down on the Earth so hard that they may be contributing to the city’s ongoing subsidence. A more recent separate study found that some buildings in Miami are sinking in part due to disruptions in the subsurface caused by construction of newer buildings nearby.

The new study found that eight cities — New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Houston, Philadelphia, San Antonio and Dallas — account for more than 60 percent of the people living on sinking land. Notably, these eight cities have experienced more than 90 significant floods since 2000, likely driven in part by lowering topography.

Some cities are seeing differential motion, with adjoining localities sinking at different rates, or even sinking while other areas rise; the upward motion possibly caused by quick recharge of aquifers near rivers or other water sources. The study found that uplift in certain areas is actually more than compensating for overall sinkage in three cities: Jacksonville, Florida; Memphis, Tennessee and San Jose, California.

Differential motion is problematic because if a whole urban area is moving up or down evenly at the same rate, that minimizes the danger of stresses to building foundations and other infrastructure, the authors noted. But if structures are subjected to an array of uneven vertical movements, they can experience dangerous tilting.

“Unlike flood-related subsidence hazards, where risks manifest only when high rates of subsidence lower the land elevation below a critical threshold, subsidence-induced infrastructure damage can occur even with minor changes in land motion,” the authors stated.

The study found that only about 1 percent of the total land area in the 28 cities lies within zones where differential motion could affect buildings, roads, rail lines and other structures. However, these areas tend to be in the densest urban cores, and currently contain some 29,000 buildings. The most hazardous cities in this regard are San Antonio, where the researchers say 1 in 45 buildings are subject to high risk; Austin (1 in 71); Fort Worth (1 in 143) and Memphis (1 in 167).

An earlier study of 225 U.S. building collapses between 1989 and 2000 found that only 2 percent were directly attributable to subsidence. The factors behind 30 percent were designated unknown, suggesting that subsidence could have played a larger role, this latest study found.

Flooding can be mitigated with land raising, enhanced drainage systems and green infrastructure such as artificial wetlands to absorb floodwaters, the researchers recommended. Cities susceptible to tilting hazards can focus on retrofitting existing structures, integrating land motions into building codes, and limiting new building in the areas of most threat.

“As opposed to just saying it’s a problem, we can respond, address, mitigate, adapt,” said Ohenhen. “We have to move to solutions.”

The study was coauthored by researchers from Virginia Tech, the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research, University of California Berkeley, Texas A&M University, University of Colorado Boulder, Brown University and United Nations University.

Original article by Kevin Krajick, senior editor for science news at the Earth Institute and the Columbia Climate School.

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes  RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit  Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk