The 7.5 magnitude earthquake that struck off the west coast of the island of Honshu in Japan on Jan. 1, 2024, will lead to an estimated $6.4 billion in total insured losses, according to Karen Clark & Company’s (KCC) high-resolution Japan Earthquake Reference Model.

Residential losses will account for over two-thirds of the total estimate loss.

The Noto Peninsula Earthquake struck 7 km north‐northwest of Suzu on the Noto Peninsula of Ishikawa Prefecture in Japan and impacted the four prefectures of Ishikawa, Niigata, Toyama and Fukui.

KCC noted it was the largest earthquake to hit Japan since 2015, and the deadliest in the country since 2016.

The earthquake was a result of shallow reverse faulting, which means that geological strata on one side of a fault plane are pushed up over the strata on the other side.

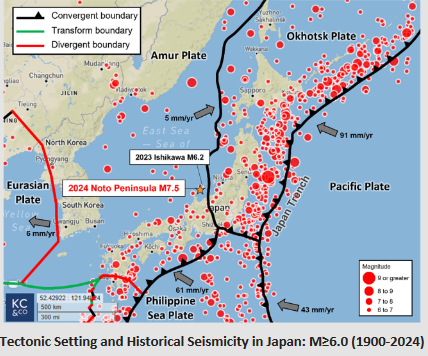

Japan typically experiences earthquakes off its east coast, where the Pacific Plate subducts beneath the country.

The occurrence on the “west coast demonstrates the accommodation of crustal deformation arising from broader plate motions in shallow faults. Shallow earthquakes like this one tend to cause more damage than their deeper counterparts due to the proximity of the released energy to the Earth’s surface,” the KCC event brief stated.

The seismic activity resulted from shallow reverse faulting within the Earth’s crust, with the USGS noting “focal mechanism solutions for the earthquake indicate faulting occurred on a moderately dipping reverse fault striking to the southwest or northeast.”

The Noto Peninsula, though a typically less seismically active region than the east coast of Japan, was most recently struck by an earthquake on May 5, 2023, when a 6.2M earthquake killed one person and damaged dozens of buildings.

KCC scientists estimate over half-a-trillion dollars of exposure to residential, commercial and industrial properties.

Homes in Machiya make up more than a third of the residential inventory in Ishikawa Prefecture, and they are especially vulnerable during earthquakes because of their heavy earthen walls, traditional timber construction, and tiled roofs which are more prone to collapse, according to the KCC analysis.

The homes there are quite narrow making them more susceptible to lateral forces during strong shaking.

The majority of the remaining residential buildings are 1‐ and 2‐story wooden buildings which are more earthquake-resistant because of their wooden frames, partially reinforced by light metal, the KCC event brief noted.

Where there was significant ground shaking, the increased resilience might not matter.

In addition, across Ishikawa, a third of all residential buildings date from before 1981, so age may impact the damage the buildings sustained.

CoreLogic estimates that insured losses due to damage from ground shaking, fires following, tsunamis and liquefaction could be between $1 billion and $5 billion.

This insured loss estimate includes damage to buildings and their contents, as well as business interruption or the costs associated with additional living expenses. Damage to residential, commercial, industrial and Kyosai structures are included. However, CoreLogic said that damage to government property, infrastructure such as road and rail networks, water and electric power systems, and oil and gas pipelines are not included.

Global credit rating agency AM Best expects minimal earnings impact on the major domestic non-life insurers related to losses stemming from this event.

The Japanese government supports residential earthquake risks through a state-backed reinsurance scheme, so most losses to domestic non-life insurers are expected to come from commercial and industrial risks, according to AM Best analysis.

The commentary adds that Japan’s insurers’ adoption of generally conservative reinsurance strategies and the low earthquake reinsurance attachment point relative to their capital positions have largely transferred earthquake risks to the international reinsurance market.

“While the earthquake losses would drag the proportional treaties results, if losses were to hit individual companies’ earthquake reinsurance excess-of-loss layers, it might fuel rate increases in the upcoming April 1 reinsurance renewal,” said Chanyoung Lee, director of analytics at AM Best.

The credit agency noted Japan’s non-life insurance segment had a benign natural catastrophe year in 2023, following a fiscal year of sizeable catastrophe losses from Typhoons Nanmadol and Talas in 2022.

Any negative impact on profitability is expected to be offset by profits from other lines of business, AM Best said.

AI Got Beat by Traditional Models in Forecasting NYC’s Blizzard

AI Got Beat by Traditional Models in Forecasting NYC’s Blizzard  AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers

AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers  Reinsurance Program Could Wipe Out Need for Calif. FAIR Plan: Legal Exec

Reinsurance Program Could Wipe Out Need for Calif. FAIR Plan: Legal Exec  Is Risk the Main Ingredient in Ultra-Processed Food?

Is Risk the Main Ingredient in Ultra-Processed Food?