The chairman of Berkshire Hathaway said that while his insurance units aren’t heavily exposed to underwriting losses from the COVID-19 pandemic, they would be willing to insure pandemics in the future.

“The answer is we insure a lot of things. Sure,” Warren Buffett said, responding to the question from a shareholder during the company’s annual meeting on Saturday. He explained that Berkshire is “famous” for offering unusual coverages, and noted that his insurance operations would have covered pandemics in the past, as well.

“We would have written pandemic insurance if people had come to us and offered us what we thought was the right price. We would have been wrong, probably, in doing it. But we have no reluctance to quote on very unusual things and [with] very big limits,” he said.

“We haven’t done that much of it in certain periods because the prices weren’t right,” he said, referring generally to large insurance bets on risks that are out of the ordinary. “But if you want to come [to] insure almost anything—we don’t want you to insure against fire if you happen to be a known arsonist or something—but if you come to us with any unusual coverages either in size or in the nature of what’s covered, Berkshire is a very good place to stop,” he said.

If someone wants to “dream up the coverage and they can tell us the price they’ll pay, [then] we will consider writing it,” he said, recalling that Berkshire and American International Group were among the few insurers that were willing to write a lot of terrorism risk insurance after the 9/11 terror attacks. “We thought we knew that we were doing, but we could have been surprised. There could have been some follow-on incidents from 9/11 that we wouldn’t have known about. You don’t know for sure the answer. That’s why people are buying insurance. But we would be willing to write pandemic coverage at the right price,” he said.

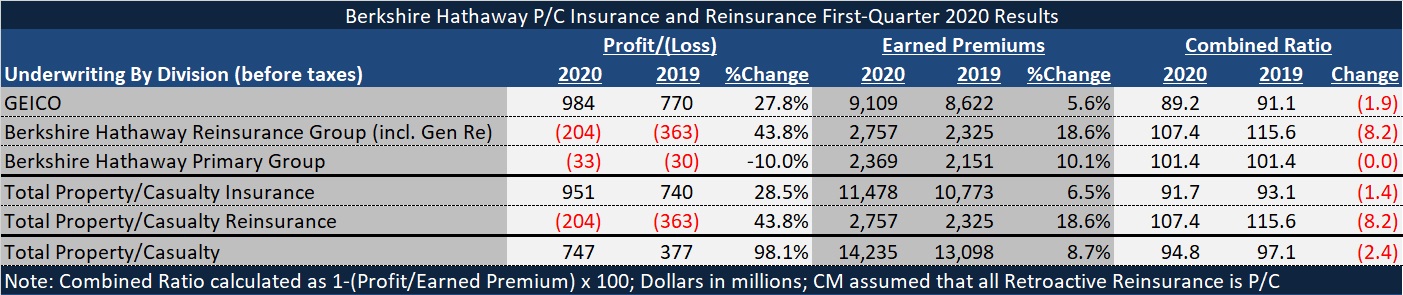

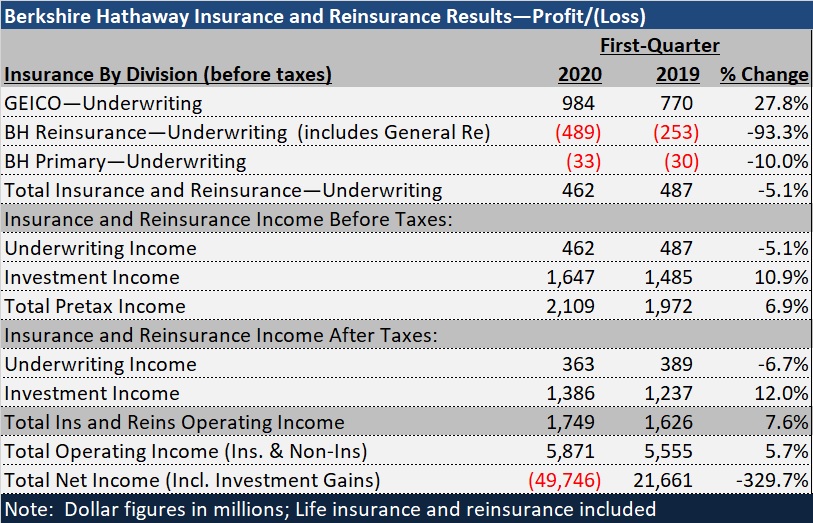

Berkshire Hathaway also reported its first-quarter 2020 earnings on Saturday, and while the report disclosed a $230 million provision for COVID-19 related reinsurance losses and prior-year loss development of $212 million in its property/casualty reinsurance business, aggregated together, Berkshire Hathaway’s insurance and reinsurance operating units for P/C and life businesses recorded $1.7 billion of operating profit after taxes in the first quarter.

Across all of Berkshire’s operations, including those not related to insurance, operating income was $5.9 billion. But unrealized investment losses of more than $55 billion meant a bottom-line loss of $50 billion.

The biggest driver of the 7.6 percent jump in insurance profit was a 12 percent increase in investment income compared to first-quarter 2019. Underwriting income fell 6.7 percent to $363 million after taxes, mainly as a result of underwriting losses recorded in Berkshire’s life reinsurance operations. For P/C insurance and reinsurance, underwriting profit was $747 million before taxes, nearly double the pretax underwriting profit of $377 million recorded for first-quarter 2019.

Although Berkshire’s 10-Q filing disclosed adverse development of $212 million in Berkshire Hathaway’s reinsurance operations, which include General Re, favorable prior-year development of $172 million at GEICO and in Berkshire’s other primary operations nearly offset that.

Berkshire’s SEC filing for the first quarter gives no further details the $230 million COVID-19 loss provision for the P/C reinsurance operations, and Buffett did not even mention it during the conglomerate’s annual meeting. But when asked about the absence of a provision for Berkshire’s insurance operations, he did note that the primary ops aren’t big providers of business interruption coverage in the commercial multiple peril line.

“We will have claims. We will have litigation costs. But proportionally, it’s not the same with us as with some other companies which are heavier in writing business interruption as part of a commercial multi-peril policy,” he said.

Speaking more generally about the state of the industry on business interruption, Buffett said that “many policies quite clearly in the contract language” would not respond to claims for businesses shut down by the pandemic.

“But other policies do. I think I know of one company, I don’t know the details, that’s written a fair amount where…certainly there’s a good argument that they cover business interruption that might arise from a pandemic,” he said, referring to the company twice without disclosing the name. “They are in a very different position than the standard language which says that you recover for business interruption only if [it] involves physical damage to the property.”

Giving a mini-lesson in business income insurance coverage, Buffett asserted, “You don’t automatically get coverage if you have business interruption,” offering two situations to illustrate how the coverage works. In one situation, he noted that one of Berkshire’s properties in France was adjacent to a smaller one that had a fire, which spread to Berkshire’s plant. “It caused a lot of physical damage, and we have business interruption that ties in with that. But if we had some company [that] we were selling auto parts to and they had a strike, our business would be interrupted. But that’s not covered. That’s not part of the coverage unless you specifically really buy it,” he said.

“So, there’s some claims that are going to be very valid related to the present situation. There will be an awful lot, [which] there will be litigation on, that won’t be valid,” he said.

Buffett fielded another insurance question related to the pandemic—the question of whether its biggest insurance operation by premium volume, GEICO, will likely experience unusually high profitability in 2020, even after giving customers a 15 percent credit to reflect reduced driving during the pandemic.

Noting the companies are handling the discounts differently, with GEICO giving 15 percent over a period of six months while other insurers are giving higher discounts over a shorter time period, Buffett asserted that GEICO’s total estimated giveback of $2.5 billion is the largest dollar amount. In addition, insurers are giving policyholders more time to pay for insurance. “If they cancel their policy or they don’t end up paying us, we’ve, in effect, given them free insurance during that period,” he said, also speculating there will be more uninsured motorists driving this year. “They cause a disproportionate amount of accidents.

“So, there’s a lot of variables. We made our best guess as to what we’re going to do to reflect the current reduced accidents in our premiums that we receive really for the next year,” he said, noting that while the discounts apply for the six months from April through October, policies renewing in October extend into April.

“We’ve made a guess on it. And we’ll see how it works out,” Buffett said.

During the first quarter, which ended prior to the start of the discount period, GEICO reported $984 million in pretax underwriting earnings, a 28 percent increase over first-quarter 2019, as written premiums grew 4.5 percent to $9.7 billion. With shelter-in-place actions already impacting claims, frequencies fell 12-14 percent for property damage and collision and 6-8 percent for bodily injury, while claim severities rose 6-9 percent for the property coverages and 4-6 percent for bodily injury.

Don’t Bet Against America

Buffett answered the questions about insurance, which would have been handled by Ajit Jain, Berkshire Hathaway’s vice chair of insurance operations, under normal circumstances. But neither Jain nor Vice Chair Charlie Munger physically attended the annual meeting in Omaha, Neb. this year—and Buffett started off his remarks by assuring livestream viewers of the event that both were safe.

Buffett and Greg Abel, Vice Chair of the non-insurance operations, sat in front of a auditorium of empty seats, and Buffett spoke uninterrupted for roughly an hour-and-a-half about the history of America and his expectations for the future. Recalling that he last sat in one of the 17,000-plus seats of that auditorium when it was packed for a Creighton-Villanova NCAA basketball game in early January, Buffett said, “There wasn’t one person there that didn’t think that March Madness wasn’t going to occur. It’s been a flip of a switch in a huge way in terms of national behavior, the national psyche,” referring to the impact of the pandemic. “It’s dramatic,” he said.

“When we started on this journey which we didn’t ask for, there was an extraordinary wide variety of possibilities on both the health side and the economic side—[with] DEFCON 5 on one side and DEFCON 1 on the other,” he said, noting that the two sides intersect and depend on each other.

“We know we’re not getting the best case. We know we’re not getting the worst case,” he said, narrowing the range of health outcomes, after admitting that he didn’t know anything more beyond that than the rest of us.

“If you were to pick one time to be born, and one place to be born, you would not pick 1720, you would not pick 1820, you would not pick 1920. You would pick today and you would pick America.”

“If you were to pick one time to be born, and one place to be born, you would not pick 1720, you would not pick 1820, you would not pick 1920. You would pick today and you would pick America.”

Bloomberg Photo (2017)

Still, Buffett said the history proves America will rise again over the long term.

“I remain convinced as I have—I was convinced of this during World War II, I was convinced of it during the Cuban Missile Crisis, 9/11 the Financial Crisis—that nothing can basically stop America.”

In the face of the toughest problems, “the American miracle, the American magic has always prevailed.”

Buffett went on to describe the history of America, taking the audience through events like the Civil War and the Great Depression—serious bumps in the road that occurred over the 231-year history of the country—which nonetheless grew from $1 billion in overall wealth (by his guess with some reference to historical records) to over $100 trillion in 2020. That is “at least $100,000 per each original $1,” he said, reading the words from one of a series of simple white slides with plain black letters and numbers.

Throughout the history lesson, he emphasized how bleak things appeared during prior crises, like the Great Depression, which started a year before he was born. The Dow Jones Industrial Average did not return to the pre-Depression level until 1951 when he finished college.

“If you were to pick one time to be born, and one place to be born, you would not pick 1720, you would not pick 1820, you would not pick 1920. You would pick today and you would pick America….Ever since America was organized in 1789, people have wanted to come here,” he said.

Emphasizing that this is a young country, based on a comparison of the 231 years since 1789 and the combined ages of Buffett and Munger (185), he said that if you had asked any of the 3.9 million living in the 13 states in 1789 what life would be like in 2020, “even the most optimistic person, even if they were drinking heavily and had a little pot” wouldn’t imagine a country with 280 million vehicles on the roads, airplanes flying people at 40 thousand feet, great hospital systems, universities, etc.

“This country has exceeded anybody’s dreams,” he said.

Although Buffett would later reveal that Berkshire recently divested of all holdings in four major airlines, Buffett repeatedly made the point that investing in America pays off over the long haul. “Never bet against America,” he had written on one of the simplest slides that summed up his view.

Since the mid-1950s, when the DJIA was around 240, “we have felt the American tailwind at full force,” he said, noting that the DJIA today is around 24,000. “You’re looking at a market today that has produced $100 to every $1—and all you had to do was believe in America and just buy a cross-section of America.”

“You didn’t have to read the Wall Street Journal. You didn’t have to look up the price of your stock. You didn’t have to pay a lot of money in fees to anybody. You just had to believe that the America miracle was intact. But you had had this testing period” between 1929 and 1954. People had lost faith. They couldn’t see the potential of what America could do,” he said.

At a later point in Buffett’s presentation, he reiterated the idea of buying a cross-section of America by recommending that individuals stick with S&P 500 index funds as investment choices.

“I don’t believe anybody knows what the market is going to do tomorrow, next week, next month. I know America is going to move forward over time,” he said, noting what we learned on Sept. 10, 2001, and a few months ago when the pandemic shut down the economy: “Anything can happen in terms of markets. You can bet on America but you have to be careful how you bet,” he said.

(Featured Photo: AP Photo/Nati Harnik)

Beyond Automation: The Emerging Role for Contextual AI in Insurance

Beyond Automation: The Emerging Role for Contextual AI in Insurance  New Texas Law Requires Insurers Provide Reason for Declining or Canceling Policies

New Texas Law Requires Insurers Provide Reason for Declining or Canceling Policies  Why Claims AI Build vs. Buy Decisions So Often Miss the Mark

Why Claims AI Build vs. Buy Decisions So Often Miss the Mark  Large Scale Cargo Ring Busted in LA, $5M Recovered

Large Scale Cargo Ring Busted in LA, $5M Recovered