Not long ago, private flood insurance was thought to be an impossible dream in the property/casualty sector. There were numerous arguments supporting the common wisdom that a meaningful market for residential flood coverage from admitted private insurers would never exist. In recent years, however, we’ve seen the private flood sector grow rapidly—growth that we believe will continue until the new market significantly closes the U.S. flood “protection gap.”

Executive Summary

Nancy Watkins and David D. Evans of Milliman provide an overview of the trends in the U.S. private flood market, with the prediction that within a few years private insurers will significantly close the protection gap by routinely offering flood coverage alongside most homeowners policies.Although the private flood market already has overcome substantial obstacles, there are more ahead.

Obstacle 1: The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is billions of dollars in debt, so doesn’t that imply its rates are inadequate? How can the private flood market profitably compete?

Flood was a peril once thought to be uninsurable by the private market, so the NFIP was created in 1968 by the U.S. government to make affordable flood insurance available to the public. Over the past 50 years, the NFIP has provided most of the primary (paying first dollar of loss) flood insurance policies purchased in the U.S. Today, some private insurers offer excess coverage over NFIP policies, but most households remain uninsured altogether for floods. In fact, according to the Insurance Information Institute’s 2018 Pulse survey, only 15 percent of U.S. homeowners had a flood insurance policy.

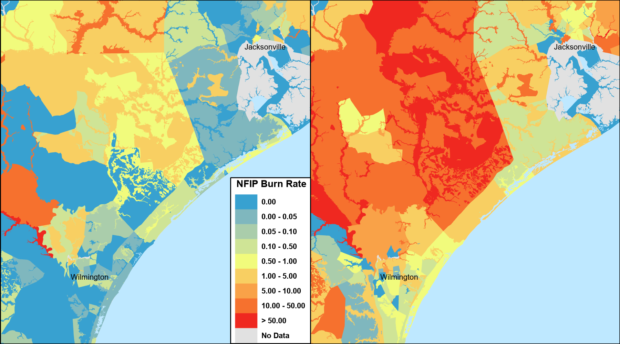

The NFIP’s debt comes from a few catastrophic years, when events like Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey generated losses vastly exceeding the NFIP’s annual premiums. This does not imply that the NFIP has inadequate premiums for every risk. For a given property, the NFIP’s rates can be high or low relative to the “true” risk, as measured using modern catastrophe models and advanced geospatial data. This is true for properties both inside the special flood hazard area (SFHA), where flood insurance is required for homes with federally insured mortgages, and outside the SFHA.

The NFIP’s rates are based on averages within very broad flood zones, and these averages are influenced by high losses on a relatively small proportion of policies. The NFIP also suffers from adverse selection—underpriced properties may be more likely to buy insurance than properties where price is high relative to the perceived risk, generating imbalances between collected premiums and expected losses.

The NFIP’s rates are based on averages within very broad flood zones, and these averages are influenced by high losses on a relatively small proportion of policies. The NFIP also suffers from adverse selection—underpriced properties may be more likely to buy insurance than properties where price is high relative to the perceived risk, generating imbalances between collected premiums and expected losses.

Private flood has competed with the NFIP through a variety of approaches. Some insurers have developed much more targeted rating schemes than the NFIP’s. Some have based their rates on the NFIP structure but employ catastrophe models to underwrite and avoid unprofitable risks. Some insurers have offered lower-limit policies outside the SFHA to attract customers who are not required to purchase flood insurance but who want the peace of mind of having coverage.

Obstacle 2: Is reinsurance and capital available for private flood?

Many insurers are not equipped to retain the risk of a catastrophic flood and need to reinsure most of the risk. However, insurers may not want to drive up the cost of their existing reinsurance programs with a new catastrophic peril or reduce their capacity to write other perils.

Spurred by the opportunity opened by congressional legislation in 2012, several global reinsurers have worked diligently to advance private flood in the U.S. Many have flood experience in other countries and are leveraging their expertise to help insurers define their target markets, model potential portfolios to understand the risk, develop flood products that appeal to consumers, create underwriting rules that reflect their risk appetite and implement sophisticated rating plans that match price to risk.

Obstacle 3: How can private flood insurers measure and manage flood risk?

For property insurance, perils driven by low-frequency, high-severity events (such as hurricanes and earthquakes) are typically measured and managed using catastrophe models that simulate a wide range of possible events and their impact on current or potential portfolios. Floods arise from hurricane storm surge and inland flooding, both on and off floodplains. Storm surge can be evaluated within hurricane models, but inland flood models were scarce until recently. Today, at least a half-dozen commercial U.S. inland flood models are available, in addition to proprietary models developed by reinsurers and other models developed for the public.

The numerous flood models available still generally vary widely on flood risk when “zoomed in” locally. Many private flood insurers and reinsurers have addressed this issue with underwriting rules that eliminate risks at locations or with attributes associated with model uncertainty and by pricing more conservatively for flood relative to well-understood perils with mature markets. Models tend to improve over time as expanded usage identifies issues and new events generate additional hazard and loss data.

Obstacle 4: Will insurers write private flood if they cannot evaluate the accuracy of catastrophe models using historical flood experience?

Validation and comparison of flood catastrophe models using actual historical experience and events has not been possible for most insurers—until June 2019, when the NFIP released 10 years of policy information and over 40 years of loss data in its “OpenFEMA” platform. In addition to property characteristics and coverages, the NFIP data contains location information at the level of latitude and longitude (approximated to protect policyholder privacy), census tract, flood zone and ZIP code. Combined together, these variables allow dissection of actual historical flood data at an unprecedented geographic level.

In addition to model validation, insurers and reinsurers can use this data to better understand which areas have prior losses and to assess the risk of small urban areas exposed to localized flooding. The NFIP data has limitations, but its release has clearly pulled back the curtain to allow insurers and catastrophe modelers a chance to further evaluate flood risk using historical experience.

In addition, the NFIP’s “Risk Rating 2.0” project is creating a more precise rating scheme, blending its own experience with catastrophe models and advanced geospatial techniques. The new rates are anticipated in 2020 for single-family homes and may make it more difficult for insurers to readily “cherry-pick,” or select against the NFIP by targeting below-average-risk policies paying average premiums. As the new rates will represent a credible measure of risk, Risk Rating 2.0 may help private flood, stimulating investment by increasing the amount of information available to insurers.

Obstacle 5: How can private flood insurers economically assess the risk for a given property?

Catastrophe models and flood rating plans rely on the data available for each risk. The geographic aspects of flood risk mostly dwarf the influence of specific property characteristics, with one important exception: first-floor height above ground. Other property characteristics are important to match price to risk, but first-floor height can be a showstopper if uncertain. The NFIP has traditionally relied on expensive elevation certificates that require a manual determination of a property’s first-floor height. In places where flood insurance is not mandatory, private flood insurance could struggle to entice consumers to purchase coverage when this substantial up-front expense is required.

So far, insurers have largely skirted the issue by writing in low-risk areas where the first-floor height is more homogeneous, or by using conservative rating factors that do not fully reflect the indicated discounts for elevated properties. For private flood to flourish more widely, it will be necessary to obtain a reasonably accurate first-floor height for most properties in a more automated way. Technological advances such as the use of light detection and ranging (LiDAR), laser inclinometers, and machine learning are making that possible.

Obstacle 6: Will mortgage lenders accept policies from private flood insurers in lieu of the NFIP?

Households with federally insured mortgages in the SFHA are required to buy flood insurance, and close to half of the NFIP’s policies are in the SFHA. Historically, it was unclear whether private flood coverage satisfied the mandatory purchase requirement, and lender compliance concerns discouraged insurers against writing the segment of the market with the highest take-up rates, premiums and awareness of flood risk.

However, this obstacle has mostly been overcome, with a final rule issued by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in January 2019 and effective July 1. Banks are now able to accept private flood insurance to satisfy mandatory purchase requirements as long as the coverage meets certain requirements. While private flood was expanding despite this past obstacle, easier lender compliance may spark further investment.

Obstacle 7: Will state insurance regulators allow private flood insurers to underwrite and price in a way that makes the opportunity worth the risk?

Admitted insurers must file private flood rates and policy forms, and sometimes underwriting rules, for regulatory review and approval in many states. Most states do not have laws that explicitly apply to private flood, leaving new programs to be evaluated against rules that were designed for residential property insurance. Homeowners insurance typically represents a mix of catastrophic and non-catastrophic perils, and in most states there is generally active competition and sufficient data upon which to base rates.

This is not the case for flood, an emerging market where most companies have little or no experience, where many of the catastrophe models are new and changing, and where almost the entire peril is from low-frequency, high-severity events. Applied to flood, these state laws and rules may be so onerous and misaligned that they unintentionally discourage private insurers from entering the market. Here are some common examples:

- Some states restrict or preclude basing rates on catastrophe models. For flood, reliance on historical experience is unlikely to provide a sound basis upon which to base rates.

- Although most insurers will rely on reinsurance to protect them against some or all of their flood risk, some states do not allow the cost of reinsurance to be reflected in rates.

- Many states have laws prohibiting insurers from non-renewing or implementing rate increases for claims occurring from catastrophes and “Acts of God.” Nearly every flood claim would fit these descriptions, handcuffing insurer actions based on individual policy experience. This is a significant issue, given that repetitive-loss properties make up only 1 percent of NFIP policies but account for more than 25 percent of the claims, according to a May 2014 FEMA report.

Regulators understand the need to serve their consumers with new private flood products in light of recent catastrophes. As a result, rates incorporating catastrophe models and reinsurance costs have been readily approved in some states where simple homeowners filings often take months. Florida passed a specific private flood law with regulator backing and input, allowing rates to be developed directly from catastrophe models, with certain consumer safeguards, until a sunset date (currently Oct. 1, 2025). Other states have also significantly deregulated flood rates, including New Jersey and, most recently, Virginia.

In many states, regulators are willing to work with companies in order to jump-start a private flood market, but they provide no explicit information about which of the normal rules are suspended or how long this suspension will last. It may not make sense for large insurers to invest in a private flood program if the rules are known for only a handful of states. Therefore, despite much regulatory cooperation, legal and regulatory uncertainty creates significant legitimate hesitation for potential market entrants.

Obstacle 8: How can private flood insurers bring potentially reluctant buyers and sellers together?

Insurance needs to be sold in order for people to buy it, but the hard truth is that flood insurance is an intimidating product for many insurance agents. The specialized knowledge needed to sell and service such a product may not justify the potential commission. Additionally, consumers struggle to understand their own individual flood risk and potential need for insurance coverage. Many infer that the mandatory purchase requirement for homes in the SFHA means that homes outside the SFHA have no flood risk and do not need coverage. Many believe their private homeowners policy covers flood risk. Other consumers simply may see “optional” flood coverage as too expensive or duplicative of post-disaster aid, which is in fact very limited. Insurers and other entities need to continue increasing their efforts to educate the public about the necessary details of flood risk and flood insurance.

Private flood insurers have a unique opportunity to start fresh and vastly simplify the agent/consumer experience. Insurers can rate properties at a resolution of only several meters, with better matching of price-to-risk, leading to greater perceived value. Agents could potentially obtain the most critical rating information instantly with just the address and the coverage amount of a policy.

There is hope that the combination of more automated processes and better pricing can reduce expenses and confusion, benefiting both agents and consumers, while consumer awareness of increasing flood risk may be building after recent high-profile flood events, such as Hurricane Harvey in Houston in 2017.

Will Private Insurers Close the Protection Gap?

We are optimistic that, in a few years, private insurers will significantly close the protection gap by routinely offering flood coverage alongside most homeowners policies. Catastrophe models will continue to improve through increased usage and additional validation against historical claims, technology will evolve to address the need for property-specific data, and additional flood events will continue to build consumer awareness and demand.

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash  AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage  Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages