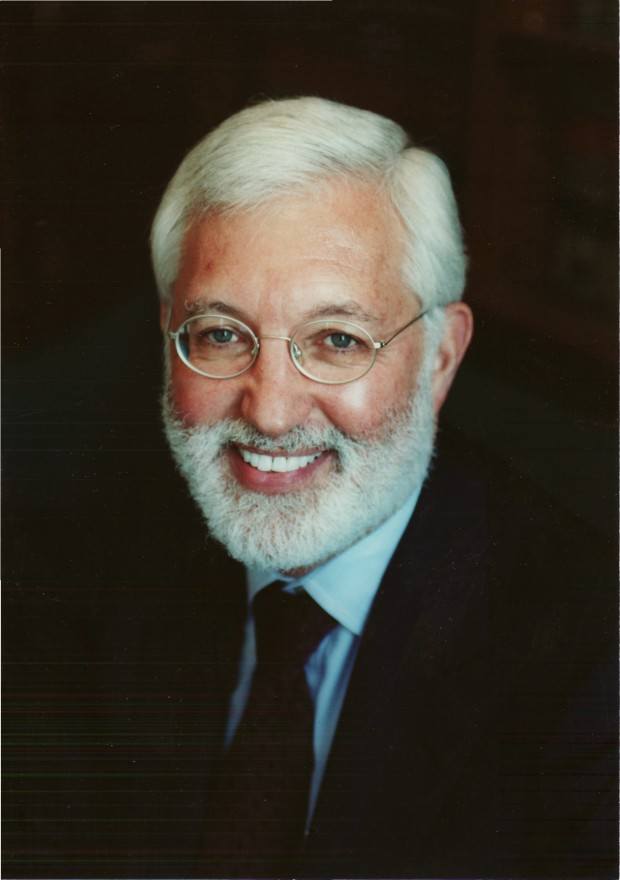

At a meeting of New York City securities lawyers last week, Jed Rakoff did what he does best: challenge Establishment Thinking. “While the economy has slowly improved, there are still millions of Americans leading lives of quiet desperation — without jobs, without resources, without hope.” Then he asked: Who is to blame?

Rakoff is the iconoclastic U.S. District Court judge who’s been at the heart of some of the most significant trials stemming from the financial crisis. And what he really wanted to know is why more there haven’t been more criminal prosecutions of top financial executives (the very ones who, not coincidentally, made many of the people in his audience quite wealthy). To Rakoff the answer, clearly, is gun-shy federal prosecutors.

The lack of prosecutions of senior financial executives “must be judged one of the more egregious failures of the criminal justice system in many years,” he said. And with a five-year statute of limitations running out, it appears “very likely” that none ever will be charged, Rakoff said.

Yes, yes, he gave all of the jurist’s usual caveats and disclaimers. “I have no opinion as to whether any given top executive had knowledge of the dubious nature of the underlying mortgages, let alone fraudulent intent,” and so on. Then he proceeded to rip apart the excuses by the Justice Department and other law-enforcers. And yes, he used the word “excuses.”

Previously, most of Rakoff’s frustration had been with the Securities and Exchange Commission. In 2011, he rejected a $285 million SEC settlement with Citigroup because it was too lenient. In 2009, he held up an SEC settlement with Bank of America until he had the information he needed to determine if it was in the public interest.

Other judges have followed his example, and this new attitude helped lead the SEC to announce earlier this year that it would no longer let white-collar defendants routinely settle cases without admitting guilt.

This time, Rakoff’s vexation is more with Justice Department officials. He explained in detail why he believes their excuses are unconvincing:

Excuse 1: Mistakes were made and, to be sure, negligence and inordinate risk-taking abounded, but that’s not the same as fraud.

Rakoff, in response, pointed to official government conclusions that intentional fraud was evident. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission’s final report mentions fraud 157 times in describing events leading to the crisis. More important, Rakoff said, simple logic tells us that fraud had to take place if dubious subprime mortgages were the sole collateral for highly leveraged securities marketed as triple A. “How could this transformation of a sow’s ear into a silk purse be accomplished unless someone dissembled along the way?” he asked.

Excuse 2: It’s difficult to prove intent by high-level managers many steps removed from the misdeeds.

How true, Rakoff said. But somehow prosecutors managed to charge junk-bond king Mike Milken and countless savings-and-loan executives in the 1980s, and a handful of top executives in the accounting scams of the 1990s, including Ken Lay of Enron Corp. and Bernie Ebbers of WorldCom Inc.

And here’s the thing, Rakoff added: Banks themselves reported cases of suspected mortgage fraud when they filed so- called suspicious activity reports in the early- to mid-2000s. With so much fraud, why didn’t managers ask why their mortgage securities continued to receive triple A ratings? This is called “willful blindness,” a condition that creative prosecutors bypass by asking juries to infer intent, especially where accounting and other esoteric concepts are involved.

Excuse 3: It’s difficult to prove that sophisticated investors who bought mortgage bonds relied on the prospectuses and sales documents.

This excuse, Rakoff said, “totally misstates the law.” In criminal cases, the government is “never required to prove such reliance, ever.” The reason is simple: Crooked sellers would have a license to lie whenever they dealt with sophisticated buyers. The law avoids this trap by assuming that sellers have purposely lied if the market as a whole has been harmed by their misrepresentations, even if the immediate purchasers weren’t.

Excuse 4: Some banks are too big to jail.

Attorney General Eric Holder said as much last year when he told Congress that criminal prosecution of a large bank “would have a negative impact on the national economy, perhaps even the world economy.” Here, Rakoff didn’t mince words, calling this excuse “disturbing, frankly, in what it says about the Department’s apparent disregard for equality under the law.” Besides, Holder’s statement is irrelevant when it comes to individual bank executives.

So, if Rakoff doesn’t buy these excuses, why does he really think prosecutors are failing to hold top executives accountable for criminal behavior that ruined the economy? I’ll outline his theories in part two of this post later.

(Dwyer is a member of the Bloomberg View editorial board.)

The Future of HR Is AI

The Future of HR Is AI  State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists

State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists  From Skill to System: The Next Chapter in Insurance Claims Negotiation

From Skill to System: The Next Chapter in Insurance Claims Negotiation  Berkshire Hathaway Profit Falls; Insurance Income Lower for GEICO, Other Ops

Berkshire Hathaway Profit Falls; Insurance Income Lower for GEICO, Other Ops