The January 2025 LA Wildfires caused unprecedented losses, but those losses should have been anticipated by insurers.

Executive Summary

The LA Wildfires caused unprecedented losses, but those losses should have been anticipated by insurers. The purpose of catastrophe models is to prepare insurers for losses that haven’t happened yet but could happen in the future. This article illustrates how the fires happened, why they were predictable, and how future fires can be worse. It also touches on likely long-term impacts.

The purpose of catastrophe models is to prepare insurers for losses that haven’t happened yet but could happen in the future. In fact, credible models reveal that future fires could be even worse.

Evolution of the Fires

The ingredients for the recent wildfires began back in winter of 2022-2023 when record-setting atmospheric rivers soaked California with over eight inches of rain in January alone. The following winter, precipitation amounts remained above normal for most of northern and southern California. After two winters of well above average rainfall, the normally sparsely vegetated hillsides around Los Angeles were abundant with lush vegetation.

The abnormally wet conditions were followed by abnormally dry conditions for southern California in 2024 with only 0.78 inches of rain falling from May to December. In normal years, October ushers in the rainy season, but the rains never arrived that fall. By December, the persistent dry conditions triggered a severe drought and the abundant lush vegetation turned into dense wildfire fuel.

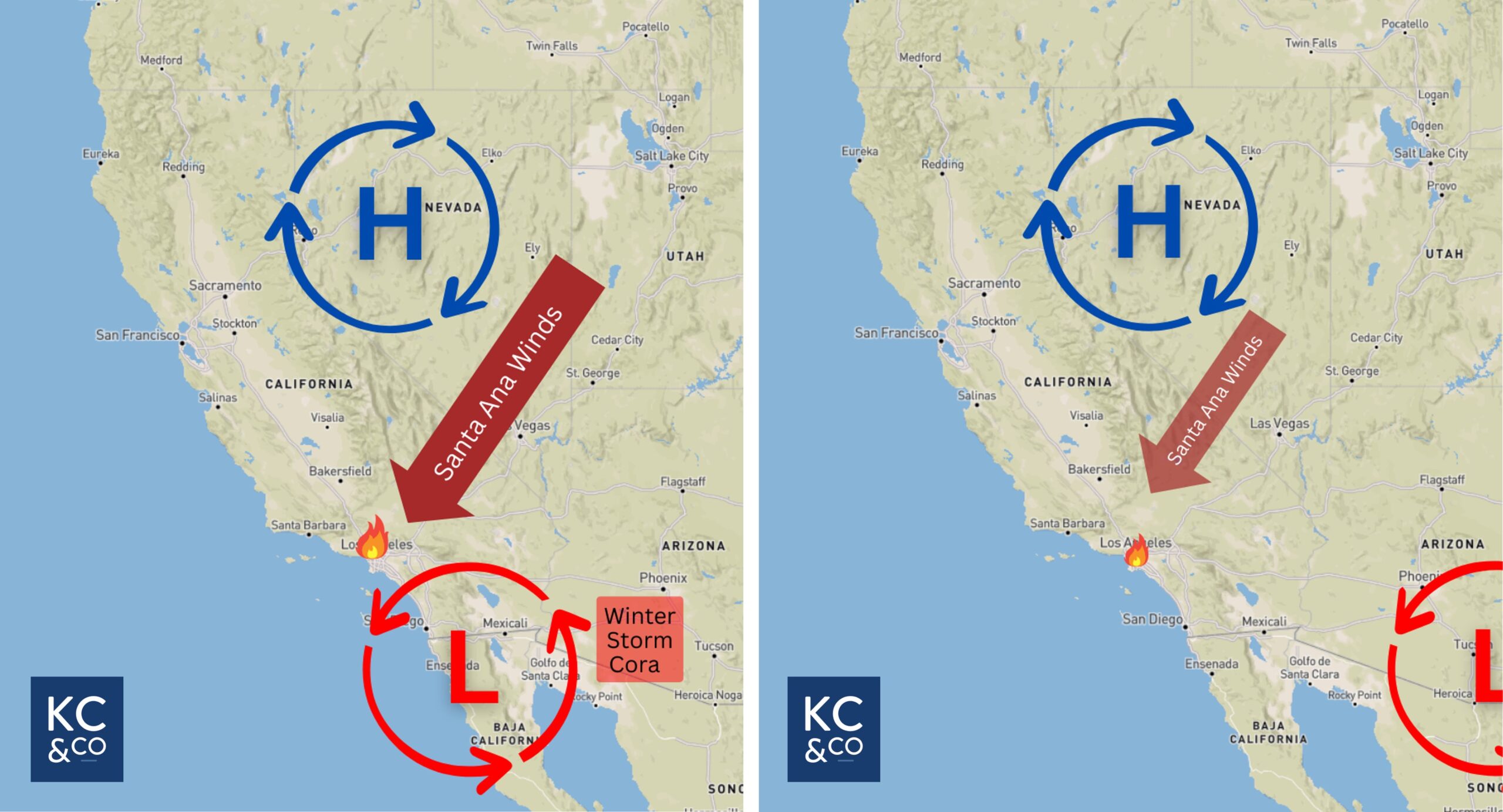

Just after the new year, on the morning of January 7, a high-pressure system settled over the Pacific Northwest accentuating a typical Santa Ana wind event.

Santa Ana winds are common in southern California, occurring nearly 20 times per year on average. But on this day a low-pressure system (that would later become Winter Storm Cora) started moving onshore near Baja California. The steep pressure gradient between the low- and the high-pressure systems accelerated the already strong winds and produced an extreme and widespread Santa Ana event with wind gusts exceeding hurricane force in multiple locations.

A fire ignited in the mountains adjacent to Pacific Palisades just after 10 a.m. and the fire expanded to 200 acres in 90 minutes. The strong winds fanned out over the Santa Monica mountains, spreading the fire down the mountain and northward toward eastern Malibu. With embers carried up to a mile away, the fire easily jumped the Pacific Coast Highway, burning hundreds of structures along the coast. The intense and fast-moving fire could not be suppressed by firefighters, and most structures in Pacific Palisades and Eastern Malibu were destroyed within 24 hours of when the fire ignited.

East of the Palisades, another fire ignited in Eaton Canyon. The Santa Ana winds steered that fire, along with an overwhelming number of embers, down the mountain toward Altadena. As the embers landed, small spot-fires cropped up across the northeast side of the city. The winds and dry fuel allowed the flames to expand outward in the mountains and engulf suburban neighborhoods. As with the Palisades Fire, suppression was not possible.

It was only when the low-pressure system moved east and became winter storm Cora, that the pressure gradient weakened and the strongest winds began to subside. This shift allowed firefighting efforts and air support to resume, but most of the damage had already been done. Like the Palisades Fire, the damage was inflicted within 24 hours of the Eaton Fire igniting.

Why These Fires Were Predictable Well in Advance

While the insured losses from these fires were unprecedented, they should have been anticipated by insurers. Most insurance and reinsurance companies use catastrophe models, and the primary purpose of a catastrophe model is to prepare insurers for losses that haven’t happened yet but that could happen.

For example, there has never been a $150 billion hurricane loss, but insurers know there could be one because of the hurricane model output which helps insurers decide how much reinsurance to buy. Credible wildfire models would have likewise prepared companies for the recent and even larger losses from wildfires in the same way the hurricane models project potential hurricane losses.

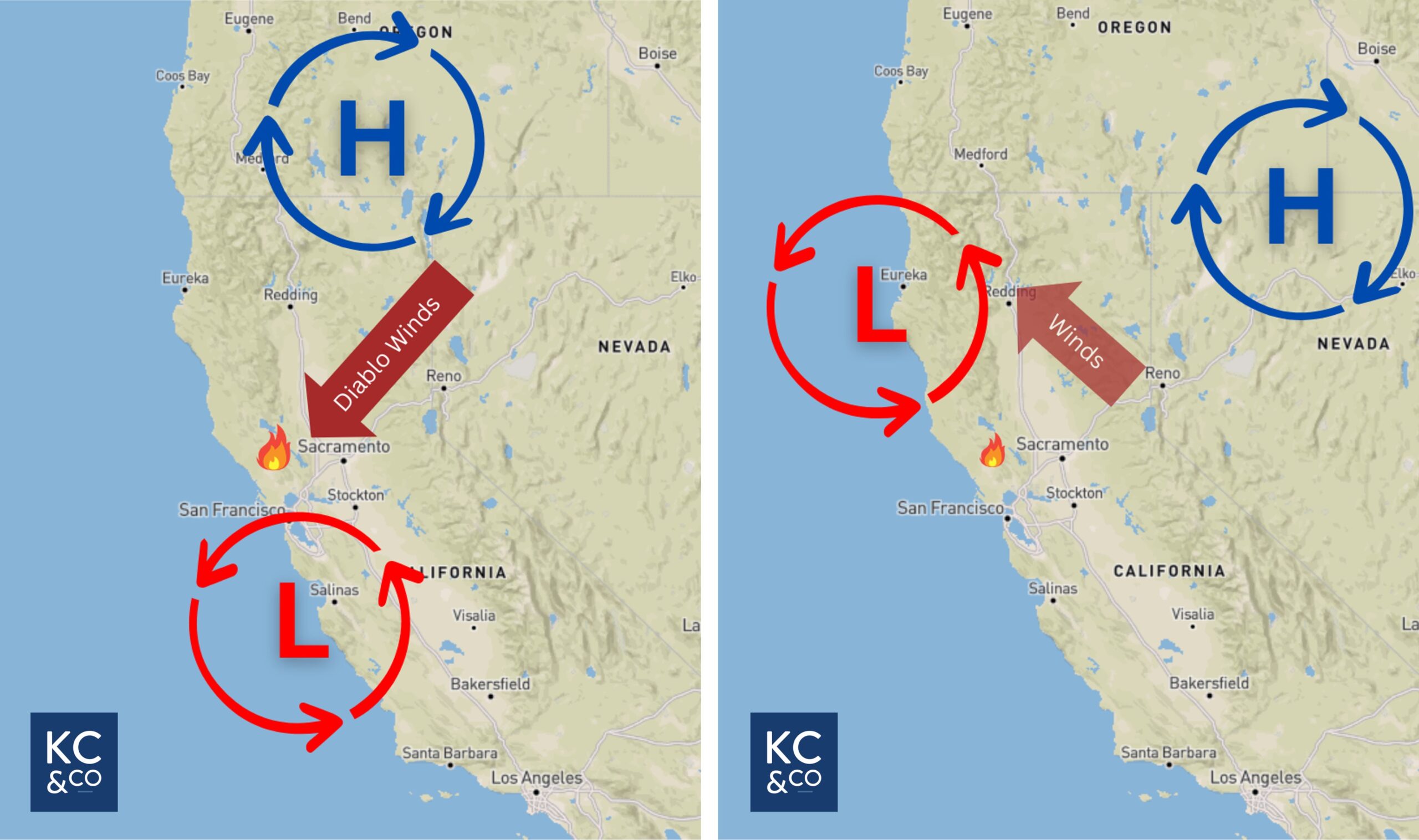

Wildfires are atmospheric perils, and the severity of a major wildfire is usually determined by the winds. The areas most likely to experience large fires and insured losses are locations prone to strong downsloping winds. These include the Santa Ana winds in southern California, Diablo winds in northern California, and Foehn winds in Colorado.

The Tubbs Fire in 2017 that resulted in a $10 billion insured loss was caused by a Diablo wind event. The fire ignited along Tubbs Lane north of Santa Rosa, Calif. when a strong downsloping event was generating wind gusts exceeding 60 mph. The winds were fueled by the same atmospheric setup as the recent LA fires—i.e., a high-pressure system over the Pacific Northwest and a low-pressure system off the coast creating a very strong pressure gradient. And just as occurred in the recent fires, the resulting strong and unpredictable winds overwhelmed firefighters, and the Tubbs Fire was only able to be extinguished after the offshore low-pressure system moved north, thereby changing the wind direction from southwest to northwest.

“While valuable for determining mitigation credits, risk scores do not provide essential information for pricing such as the true risk-based premiums or the tools insurers need to manage aggregations.”

The Tubbs Fire burned the community of Coffey Park within 10 hours of the fire ignition and—had the winds not stopped—would have gone on to destroy other areas in Fountain Grove. KCC scientists frequently used the Tubbs Fire as an example of how larger losses could occur. If the low-pressure system had not moved—allowing the fire to spread for another 12 hours—KCC scientists estimated the insured losses would have exceeded $30 billion. A more extreme, longer-lasting Diablo event could have caused $50 billion in insured losses.

These scenarios, along with numerous other large loss scenarios in southern California and across the U.S. are included in the model.

Where Else Can Insurers Expect Large Wildfire Losses?

Large wildfire losses can occur anywhere humidity is low, vegetation is dry, and strong winds are present. Locations subject to downsloping winds are particularly vulnerable because when winds descend, the air warms, dries, and can accelerate quickly.

“Climate change is increasing both the frequency and severity of wildfires across the U.S., meaning areas that don’t often experience wildfires could see major events in the future.”

For example, the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains sets up the Foehn downsloping winds that occur regularly each year, typically in the fall and winter. On the morning of December 30, 2021, an enhanced Foehn wind event was positioned over Boulder County, Colo. The winds were unusually high due to the positioning of the jet stream directly above, which produced wind gusts over 100 mph at the surface. Firefighters responded immediately to an ignition about two miles south of Boulder, but the winds made fire containment impossible. Over the next 11 hours, the fire destroyed over a thousand homes in Superior and Louisville.

That night, the winds ceased and almost a foot of snow coated the fire. Had the winds not subsided and the snow not fallen, the Marshall Fire could have easily burned several additional neighborhoods.

Moving east, downsloping winds occur along other mountain ranges, such as the Appalachians, which spread the Chimney Tops 2 fire into Gatlinburg, Tenn. Cold dry fronts along the Atlantic coast can also drive large wildfires into populated areas.

Climate change is increasing both the frequency and severity of wildfires across the U.S., meaning areas that don’t often experience wildfires could see major events in the future.

Long-Term Impacts of the Palisades and Eaton Fires

The Palisades and Eaton Fires will no doubt increase demand for insurance and reinsurance covering wildfire losses. While the KCC Wildfire Model had accurately estimated the loss potential well in advance, not all insurers believed the magnitude of the modeled losses. The recent tragic events are validations of the model and reminders that past losses are not necessarily reflective of the future. Forward-looking models are essential tools for insurers and reinsurers.

Just before the wildfires occurred, the California Department of Insurance had begun a process to allow the use of the wildfire models. To date, insurers have been allowed to use risk scores but not the full probabilistic catastrophe models for pricing and underwriting. While valuable for determining mitigation credits, risk scores do not provide essential information for pricing such as the true risk-based premiums or the tools insurers need to manage aggregations. The process to approve wildfire models will likely be expedited in response to the recent events.

Looking Ahead

The CDI has every incentive to make the rebuilding process as quick and painless as possible, both for residents as well as the insurance industry. The CDI now has the opportunity to show they’re making the right changes to pave the way for a robust private market for wildfire insurance.

There was enough evidence before the recent tragic fires that this size and larger losses were not only possible, but likely. With respect to the models, most, but not all, will now require major updating to reflect the true wildfire loss potential. The fires will open new market opportunities for insurers and reinsurers who have the right tools and are therefore confident in their ability to accurately price and manage the risk.

There’s no such thing as a bad risk, there’s only a bad price.

Featured image: AI-generated Adobe Firefly

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes  Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk  Earnings Wrap-Up: AXIS Expanding Insurance Biz, Shrinking Re Book

Earnings Wrap-Up: AXIS Expanding Insurance Biz, Shrinking Re Book