The growth of short-line and regional railroads over nearly three decades, coupled with safety advancements, have fueled new opportunities for specialty insurers in the United States—and a new administration in Washington is signaling even more promise ahead.

Executive Summary

Aspen Opinion: David Adamczyk argues that while the Trump administration’s pledge of infrastructure investment and support for fossil energy may bode well for the rail freight industry, the U.S. government has already played a key part in the revitalization and growth of the short-line and regional railroads. The Staggers Act (1980) marked the beginning of this upward trend, but more recent collaboration with government and the emphasis on safety has been a welcome development.In addition to government activity, rail industry groups are testing the results of advanced technologies ranging from laser-based track inspection to drone inspections of remote rail lines, giving insurance underwriters greater insights into accident potential.

Deregulation, Divestment and Diversification

The Trump administration’s pledge of infrastructure investment and support for fossil energy bodes well for the rail freight industry. The U.S. government has, in fact, already played a key part in the revitalization of short-line and regional railroads, starting with The Staggers Act in 1980. The act greatly reduced a federal regulatory burden that had overshadowed the industry previously.

Indeed, this legislation has been identified as the inflexion point for the resurgence of short-line rail roads. The existence of short-line operators may principally be explained in terms of origination or termination of goods’ journeys, but their significance has grown. In 1980, short-line rail accounted for 8,000 miles of track; according to the American Short Line and Regional Rail Association, this currently stands at 50,000 miles of track, or 40 percent of the U.S. rail network. Class II and Class III—short-line and regional railroads, respectively—account for 31 percent of U.S. freight rail mileage and 10 percent of employees.

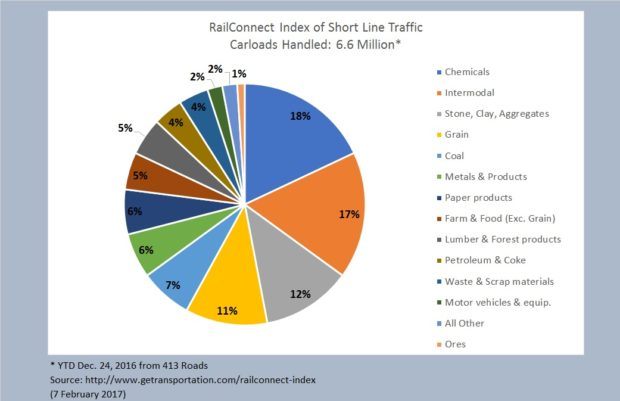

The accompanying chart shows a split of short-line freight in 2016.

Deregulation principles enshrined in the act enabled rail operators to reconfigure their networks. The large, Class I operators were encouraged to divest uneconomic, light-density lines, and the majority were purchased by independent businessmen keen to serve their regional markets and protect the short-line network. Entrepreneurial energy, coupled with an appetite for investment and risk, injected new life into the business of rail transportation. Most railroads own their tracks, but by the beginning of the 1980s, these assets were often in poor condition, reflecting years of underinvestment in these smaller lines. Insurers were presented with a highly fragmented business with relatively small exposures, sometimes limited to as little as 100 yards of connecting track, where the concept of a safety culture was inadequate.

The short-line industry’s ability to access capital became a concern in the early 1990s and marked a new stage in short-line and regional rail development. The proliferation of small freight carriers featuring highly local entrepreneurs was consolidated through the creation of holding company structures with stronger balance sheets. These newly formed companies were able to reduce the risk profile of the business through diversification of both product and geography, which in turn reduced the cost of capital for investment. Investment in talent and equipment could be optimized across a number of short-line railroads. The emergence of the holding company structure brought new challenges for underwriters as the potential loss exposures increased.

Safety Culture Support

There has been a growing realization that safety is a key priority for all rail stakeholders—including the government, employers, employees, customers and insurers—and that potential losses may extend well beyond the immediate cost of any particular incident. Added costs include reputational damage, and a poor safety record can literally stop a rail freight company in its tracks. Stronger holding company balance sheets and federal government initiatives have paved the way for greater investment in safety measures.

Class II and Class III railroads are defined by the Surface Transportation Board (STB) based upon the level of revenues earned in a year.

According to the 2013 classification, those railroads with revenues of between $37.4 million and $467.0 million are classified as Class II; a Class III railroad is defined as one with operating revenues below $37.4.

Class II carriers are typically referred to as regional railroads and often operate across several states, while Class III are often referred to as short-line railroads and serve a smaller geographic area.

Regardless of operation size, these carriers fill a critical need by connecting their customers to the Class I rail network. In many cases, Class III railroads provide rural communities with an important transportation link to the national rail network to move goods both in and out of these areas, and many are now owned by holding companies. In this report, short-line rail includes both Class II and Class III.

The Railroad Track Maintenance Tax Credit, also known as the 45G Tax Credit, is one such example of a federal government initiative. This was introduced for track maintenance conducted by short-line and regional railroads. It became effective in 2005 with an initial expiration date of 2009, although it has been variously extended—most recently until December 2016. The 45G Tax Credit granted an amount equal to 50 percent of qualified track maintenance expenditures and other qualifying railroad infrastructure projects. The rail industry is now lobbying for this tax credit to be permanently reinstated and is hopeful given its compatibility with the administration’s belief in providing fiscal incentives to encourage growth and infrastructure investment.

A strong safety culture is paramount for continued improvements. In 2015, the Short-Line Association partnered with U.S. Congress and the Federal Railroad Administration to establish a Short Line Rail Safety Institute, which assesses the practices and culture of individual short lines and provides support to improve workplace safety. The initiative is built on four pillars: safety culture assessment, education and training, communication and research to deliver safety education and products. The initiative is important because it monitors the safety standards of small carriers and holding companies to ensure they are applied consistently. The institute’s pilot phase to assess and address safety culture gaps was completed in mid-2016.

New Technology Initiatives

Identification, assessment and prevention play a critical part in the process of risk management, and the application of new rail technologies has provided a considerable boost. As trackside and truck and locomotive monitoring systems are continually developed, resulting big data can be analyzed. These developments enable improvements in railroad safety and risk management. Drones, for example, have been deployed for more remote and inaccessible railroad lines. Analysis of the subsequent information gives underwriters a better understanding of the risks and potential accidents.

Reduction of accident risk is a mutual goal of both railroad companies and underwriters alike, and the Transport Technology Center, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Association of American Railroads, has designed a number of preventive measures. A prototype of the world’s first laser-based inspection is being built together with a new in-motion rail joint inspection system. Onboard systems can already analyze track geometry and truck responsiveness, but track stability is being enhanced through improved metallurgy and fastening systems and the development of ground-penetrating radar and terrain conductivity sensors. These measures help to reduce the risk of derailment, and applications dealing with rail steels, bridge-welding and specialized components have been developed to cope with the risks associated with the use of heavier and longer trains.

In terms of rolling stock, a relatively small proportion of freight trucks cause a disproportionate amount of damage and also have a higher propensity to derail, and so new detectors are being developed. Meanwhile, new locomotives often have 20 or more microprocessors to monitor critical function and performance.

Increased investment in the short-line and regional railroad networks has been a main factor in the decline of train derailments. As the frequency of incidents has diminished, attention has not surprisingly turned to the severity. Parallels with the aviation industry have been drawn given it is an industry with zero tolerance for incidents. This must, likewise, be the goal for the railroad industry and underwriters alike, and new technology is playing an important role.

(Editor’s Note: A version of this article was published on Aspen’s website.)

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk  Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster