Automakers intending to bring driverless cars to market need to work as much on software design as mechanical engineering, the researcher leading Nissan Motor Co.’s automated-vehicle program said.

Making cars that are “deliberative” in assessing road conditions, rather than just reactive, requires artificial intelligence, Maarten Sierhuis, director of Nissan’s Silicon Valley research center in Sunnyvale, Calif., said in an interview. The carmaker, which aims to sell vehicles that can drive themselves by 2020 or sooner, is developing software to read and filter sensor data much as a human brain does, he said.

“What the auto industry has to come to is a shift from thinking about the car as a physical, mechanical system,” Sierhuis said in an interview last week at the Automated Vehicles Symposium in San Francisco. “Autonomy, autonomous systems, is about understanding how humans do that, and then replicating it with software.”

Carmakers and parts manufacturers including Nissan, Toyota Motor Corp. and Daimler AG, along with technology companies such as Google Inc., are accelerating research into systems that can make driving partly or fully automatic. Benefits include eliminating traffic accidents and congestion, reducing fuel use, and opportunities for people to use the time in transit for activities other than driving.

Traffic accidents kill more than 30,000 people annually in the U.S. While regulators in the U.S. see potential benefits for improved safety from autonomous vehicles, regulatory and legal issues such as liability in accidents have yet to be addressed.

‘A.I. Thinking’

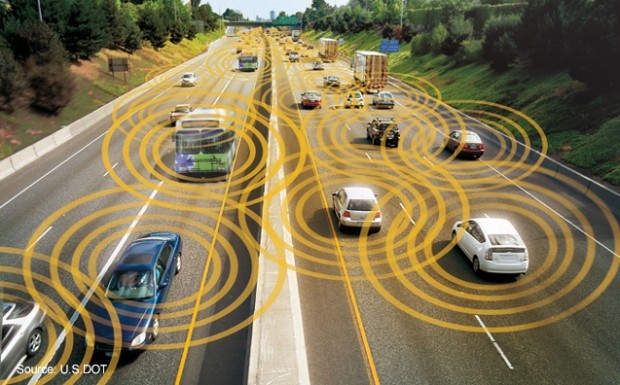

President Barack Obama last week highlighted U.S.-backed research on technology being developed by carmakers to allow vehicles to communicate with each other to reduce traffic jams and accidents.

Automation features such as adaptive cruise control, blind- spot monitoring and lane-keeping assistance aren’t sufficient, said Sierhuis, a computer scientist who designed software for NASA space missions.

“It’s a matter of also understanding the roads, understanding the situation, understanding other objects and knowing what to do with that information,” he said. “To plan your path around it needs deliberation –A.I. thinking.”

Nissan’s lab in Sunnyvale, with about 20 engineers, finds small Silicon Valley startups that can supply new types of sensors and components needed for the Yokohama, Japan-based company’s autonomous-vehicle program, Sierhuis said.

Google said in May it would put at least 100 autonomous cars it designed in trials starting this year. The two-seat cars have a top speed of 25 miles (40 kilometers) an hour and no steering wheels, brakes or accelerator pedals.

While Google hasn’t said if it will sell such vehicles, “I’m confident Nissan can have autonomous vehicles ready by the end of the decade,” Sierhuis said.

Toyota Scientist Weighs In on Pollution Issues

At the same event, Automated Vehicles Symposium, Bloomberg also interviewed a Toyota scientist, who said the appeal of autonomous cars carries the risk of adding to urban sprawl and pollution as they may encourage commuters to travel farther to work.

Technologies that let a driver turn vehicle controls over to the car itself should begin arriving late this decade, said Ken Laberteaux, senior principal scientist for Toyota’s North American team studying future transportation. Faster commutes can bring unintended consequences, Laberteaux said in an interview at the Automated Vehicles Symposium in San Francisco last week.

“U.S. history shows that anytime you make driving easier, there seems to be this inexhaustible desire to live further from things,” Laberteaux said. “The pattern we’ve seen for a century is people turn more speed into more travel, rather than maybe saying ‘I’m going to use my reduced travel time by spending more time with my family.'”

Toyota and other auto manufacturers, along with technology companies such as Google Inc., are accelerating research into systems to partly or fully automate driving. While benefits could include eliminating traffic accidents and congestion, and in turn cutting fuel use, driverless technology may also result in people using their cars as mobile offices during commutes.

U.S. regulators are encouraging development of automated vehicle systems to reduce traffic accidents that annually kill more than 30,000 people. Regulatory and legal issues with self- driving cars, such as liability in accidents, have yet to be addressed and are among the topics being discussed at the San Francisco conference.

Co-Pilot Approach

Toyota has said it favors more of a “co-pilot” approach to automated vehicles, rather than a driverless system. The Toyota City, Japan-based carmaker, the world’s largest, hasn’t said when it will sell the vehicles.

Local governments could take steps to avoid lengthier commutes by drivers of autonomous cars through the use of tolls, for example, Laberteaux said. Such steps also tend to be unpopular in the U.S.

“We’ve created an entire culture and economy based on the notion that transportation is cheap,” he said.

Large Scale Cargo Ring Busted in LA, $5M Recovered

Large Scale Cargo Ring Busted in LA, $5M Recovered  State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists

State Farm Inked $1.5B Underwriting Profit for 2025; HO Loss Persists  Machine Learning for Mutuals: What’s Working, What’s Not, and What’s Next

Machine Learning for Mutuals: What’s Working, What’s Not, and What’s Next  New Texas Law Requires Insurers Provide Reason for Declining or Canceling Policies

New Texas Law Requires Insurers Provide Reason for Declining or Canceling Policies