If you are shocked and surprised that your Crunch Berries have no berries, your Froot Loops contain no fruit and your “all natural” ice cream contains genetically modified organisms (GMOs), you’re probably not dismayed over the rash of class action lawsuits attacking the food and beverage industry’s labeling practices over the past several years.

Executive Summary

Over the past year, there have been several significant court decisions relating to class certification that give rise to optimism that the tide of food and beverage labeling lawsuits may be turning in favor of food manufacturers and their insurers, according to Cozen O’Connor’s Richard Fama and Brenden Coller.If you are like most of us, however, you are likely scratching your head wondering what is behind this all-out assault on the products we know and love and when it will all end.

Driven primarily by well-funded plaintiffs’ lawyers looking for the next asbestos or tobacco (pick your poison), an increasingly health-conscious population and inaccurate media portrayals of the safety of GMOs, these so-called false labeling lawsuits will likely continue to challenge us well into the future. And although many of these lawsuits sound comical and are often the subject of late-night talk show jokes, the burden on the industry and its insurers—in terms of litigation costs, settlements, lost productivity and impact on brand reputation—is undeniable.

Driven primarily by well-funded plaintiffs’ lawyers looking for the next asbestos or tobacco (pick your poison), an increasingly health-conscious population and inaccurate media portrayals of the safety of GMOs, these so-called false labeling lawsuits will likely continue to challenge us well into the future. And although many of these lawsuits sound comical and are often the subject of late-night talk show jokes, the burden on the industry and its insurers—in terms of litigation costs, settlements, lost productivity and impact on brand reputation—is undeniable.

There are many things manufacturers can and should do (and their insurers should advocate for) to avoid becoming the target of litigation: implementing robust safety procedures, staying abreast of trends in food and beverage-related litigation, and routinely evaluating product labeling to ensure compliance with governmental regulations, to name a few.

Given the present landscape, however, even the most innocuous statement on a label can expose a manufacturer to a class action lawsuit and multiple copycat lawsuits. It is therefore critical for food manufacturers, distributors and retailers—and those that insure them—to understand the complexities and nuances associated with food labeling litigation and how to effectively manage class action lawsuits.

To be sure, there are a multitude of litigation strategies that manufacturers can employ to efficiently and successfully defend against false labeling lawsuits, each of which can be the subject of its own article. The primary battleground, however, lies at the class certification stage, where the plaintiff seeks the court’s approval to bring the suit on behalf of all consumers—often nationwide.

Over the past year, there have been several significant court decisions relating to class certification that give rise to optimism that the tide may be turning in favor of food manufacturers and their insurers.

Ascertainability

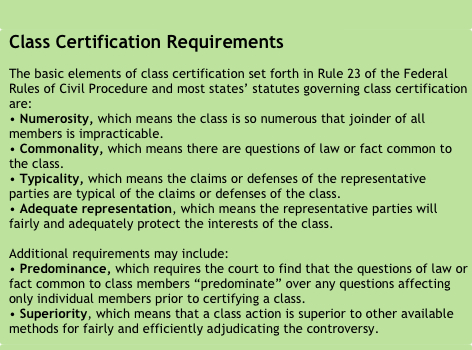

Many lawyers can easily recite the basic elements of class certification set forth in Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and most states’ statutes governing class certification: numerosity, commonality, typicality, adequate representation and, often, the additional requirements of predominance and superiority. (See related textbox, “Class Certification Requirements.”)

For years, these elements defined the battleground for determining whether a class should be certified. And although they remain in the spotlight, courts have recently begun to focus on the implicit prerequisite to class certification: ascertainability.

Although not specifically mentioned in Rule 23, ascertainability requires the proponent of the class certification to prove that members of the putative class can be easily identified through objective criteria.

Attendant to this requirement is a defendant’s undeniable due process right to challenge the elements of a plaintiff’s claim and, more specifically, class membership.

In a non-class action suit, it is undeniable that a plaintiff is required to prove the elements of the claim, and the defendant has the right to challenge the plaintiff’s proof (i.e., cross-examine the plaintiff or challenge the authenticity of a document). The ascertainability requirement ensures that the parties’ respective rights and responsibilities are extended and applied equally to class action litigation.

Courts nationwide have increasingly required proponents of class certification to answer the question of how they intend to prove that members of the purported class can be easily identified using objective criteria. This question is relatively simple to answer when the product involved is a major purchase such as a new car, where the manufacturer, auto dealership, finance company and relevant governmental agencies will have records to identify purchasers.

Courts nationwide have increasingly required proponents of class certification to answer the question of how they intend to prove that members of the purported class can be easily identified using objective criteria. This question is relatively simple to answer when the product involved is a major purchase such as a new car, where the manufacturer, auto dealership, finance company and relevant governmental agencies will have records to identify purchasers.

This question is much harder to answer, however, in class action lawsuits against manufacturers of lower dollar value consumer goods, such as food items, because manufacturers often do not sell directly to consumers and possess little to no information to identify those individuals who actually purchased their goods. And because food products are generally of lower dollar value, consumers are unlikely to keep receipts or other forms of proof of purchase.

This low dollar value, recordless type of transaction is at issue in virtually every mislabeling action, making ascertainability a key defense for manufacturers.

In Carrera v. Bayer (3rd Cir. 2013), the plaintiff sought to bring a false advertising claim relating to Bayer’s One-A-Day WeightSmart product on behalf of all persons who purchased the product in Florida. After the court acknowledged that Bayer had no list of consumers that purchased the product, and it was unlikely that consumers would have any proof of purchase, the plaintiff argued that he could show an ascertainable class through: 1) retailer records, including those related to the use of shopper loyalty cards; and 2) affidavits from absent class members attesting that they purchased the product for a specified amount.

Responding to the plaintiff’s arguments, the court stated that a plaintiff must produce evidentiary support that the method of ascertaining a class will be successful and “administratively feasible,” and that the method cannot result in individualized questions or “mini-trials” to prove class membership.

Based upon the proof offered by the plaintiff in support of class certification, the 3rd Circuit held that he failed to adequately demonstrate that retailer sales records were an objectively reliable and administratively feasible method of determining class membership.

The court also rejected the argument that affidavits from absent class members could be used as a method to identify class membership because it “does not address a core concern of ascertainability: that a defendant must be able to challenge class membership.”

Highlighting the constitutional safeguards provided by the ascertainability requirement, the Carrera court further stated that “ascertainability provides due process by requiring that a defendant be able to test the reliability of the evidence submitted to prove class membership” and that a “defendant has similar, if not the same, due process right to challenge the proof used to demonstrate class membership as it does to challenge the elements of a plaintiff’s claim.”

Although other courts have addressed the ascertainability argument and come to similar conclusions, it is undeniable that the Carrera decision is a powerful arrow in the quiver of the defense bar. When defending a false labeling lawsuit and determining the likelihood of class certification, it is imperative that one objectively analyze whether a reliable and administratively feasible method of determining class membership exists.

Although the burden for class certification generally lies with the plaintiff, if no such method appears to exist, the defense practitioner should frame discovery with a focus on defeating class certification on ascertainability grounds, such as by obtaining receipts, canceled checks, credit card statements and shopper loyalty records of class representatives and, if possible, absent class members.

Manufacturers’ own internal records might also support a lack of ascertainbility. For example, a manufacturer’s consumer affairs data may contain records demonstrating that consumers generally do not retain receipts and are often confused over the exact products that they purchase.

Typicality

Any manufacturer that has been the target of a false labeling claim knows all too well the surprise of receiving a complaint that implicates dozens of products when the plaintiff only purchased one of them.

There are multiple avenues through which a defendant can push back and attempt to limit its exposure to the number of products (and thus damages) subject to suit.

Courts, however, are split regarding when and how defendants can attack this issue (as noted in Vasic v. Patent Health LLC, S.D. Cal. March 10, 2014). One line of cases holds that a plaintiff is subject to a motion to dismiss for lack of standing for any products he or she did not purchase. Manufacturers and their insurers facing suits in jurisdictions adopting this line of cases should consider filing an early motion to dismiss.

The second line of cases allows a plaintiff to bring suit for purchased and unpurchased products if they are “substantially similar.” Courts have found that products are “substantially similar” when they are “physically similar” and when the “differences between the purchased products and unpurchased products do not matter because the legal claim and injury to the consumer is the same.” (Ang v. Bimbo Bakeries USA Inc., N.D. Cal. March 13, 2014).

The last line of cases defers the decision until class certification and analyzes whether the plaintiff’s claims are “typical” of those of the rest of the class. As this article focuses on defenses to class certification only, the last of these approaches will be discussed.

In Major v. Ocean Spray Cranberries Inc. (N.D. Cal. June 10, 2013), the United States District Court for the Northern District of California decided whether a class could be certified where the representative plaintiff did not purchase all of the products at issue. Finding that the plaintiff’s claims were not typical of the claims of her putative class, the court denied class certification.

In Major v. Ocean Spray Cranberries Inc. (N.D. Cal. June 10, 2013), the United States District Court for the Northern District of California decided whether a class could be certified where the representative plaintiff did not purchase all of the products at issue. Finding that the plaintiff’s claims were not typical of the claims of her putative class, the court denied class certification.

In Major, the plaintiff brought claims that the defendant’s beverages were falsely labeled as “no sugar added” and “free from artificial colors, flavors or preservatives,” as well as “healthy” and a “source of an antioxidant or nutrient.” The plaintiff alleged that she purchased five of the defendant’s products: (1) Blueberry Juice Cocktail, (2) 100% Juice Cranberry Pomegranate, (3) Diet Sparkling Pomegranate Blueberry, (4) Light Cranberry and (5) Ruby Cherry.

The plaintiff presented the court with two different sets of classes: one in her complaint, and the other in her briefing for class certification. In her complaint, the plaintiff defined the class to include purchasers of products that contained specific alleged misrepresentations (i.e., labeled “no sugar added” or represented to contain no artificial colors, flavors or preservatives). In her motion for class certification, however, she sought certification of classes of purchasers of any product from a number of the defendant’s “product lines”: “100% Juice,” “Juice Drinks,” “Sparkling” and “Cherry.”

Declining to certify the class on typicality grounds, the court found that both classes “vaguely refer to a variety of the defendant’s products and do not identify specific and particular products that were alleged to have been purchased by the plaintiff.”

The court’s primary basis for finding that typicality was lacking was that the proposed classes were “so broad and indefinite that they encompass products that [the plaintiff] herself did not purchase” and “would…encompass a whole host of other products that the plaintiff had nothing to do with.”

The court’s primary basis for finding that typicality was lacking was that the proposed classes were “so broad and indefinite that they encompass products that [the plaintiff] herself did not purchase” and “would…encompass a whole host of other products that the plaintiff had nothing to do with.”

Because of this, the court noted that the plaintiff failed “to link any of those products to any alleged misbranding issue let alone making an allegation that the plaintiff purchased all of the products in these product lines.”

Further addressing the lack of typicality, the court noted that each of the defendant’s products may have “unique” labels and nutrition claims. Using the plaintiff’s purchase of the Diet Sparkling Pomegranate Blueberry drink as an example, the court noted that the plaintiff sought to certify a class of consumers who purchased any product in the “Sparkling” product line. The court acknowledged that the plaintiff’s claim relating to the Diet Sparkling Pomegranate Blueberry drink was based, at least in part, on the fact that the label referenced blueberries. However, the plaintiff sought to certify a class of purchasers of all products in the “Sparkling” product line, regardless of whether the product label referenced blueberries.

As noted by the court, “In other words, the content that purportedly gives rise to the plaintiff’s claims is unique to the specific and particular product she purchased and has no applicability to other products within the same line.”

Defendants should pay special attention to the scope of the plaintiff’s proposed class and the products encompassed by the class definition. Depending on the jurisdiction, the fact that the representative plaintiff did not purchase all of the products at issue may be raised at the pleading stage, class certification stage or both.

No matter what jurisdiction, Major highlights the importance of carefully examining the class definition and looking closely at the products it can potentially encompass. The broader the definition and the more products it encompasses, the more likely it is that the plaintiff did not purchase all of them. Differences in packaging, representations, marketing and even ingredients could mean the difference between a class action of one product versus 12—and an individual action involving one plaintiff versus a certified class.

Predominance

Rule 23(b)(3) requires that prior to certifying a class, the court find that the questions of law or fact common to class members “predominate” over any questions affecting only individual members.

In order to fully appreciate the predominance arguments available to defendants, however, it is important to understand the manner in which consumer class actions—particularly false labeling claims—are typically brought.

False labeling claims are often brought on behalf of a class of consumers of a particular state, consumers of multiple states or consumers nationwide. Even in multistate or nationwide consumer class actions, however, representative plaintiffs frequently seek to apply a single state’s consumer protection laws—often California—to all class members.

This tactic begs the question of why one state’s consumer protection statutes should apply to consumers in other states who neither resided nor purchased the product at issue there.

The United States 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Mazza v. American Honda Motor Co.(9th Cir. 2012) addressed this very issue and concluded that because not all consumer protection statutes are created equal, a putative nationwide class could not be certified on predominance grounds.

The United States 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Mazza v. American Honda Motor Co.(9th Cir. 2012) addressed this very issue and concluded that because not all consumer protection statutes are created equal, a putative nationwide class could not be certified on predominance grounds.

In Mazza, plaintiffs from Florida and Maryland brought claims on behalf of a nationwide class of consumers under California’s consumer protection statutes for alleged misrepresentations regarding the defendant’s advertisements of a braking feature that was available on certain automobiles.

In reversing the district court’s decision to certify a class, the 9th Circuit concluded that California’s consumer protection statutes could not be applied to a nationwide class of consumers. Rather, the laws of the states in which each purported class member’s transaction took place (i.e., place of purchase) should apply.

Due to the differences among the various states’ laws applicable to each transaction on various issues, the 9th Circuit found that Rule 23’s predominance requirement was not satisfied. Accordingly, the nationwide class was decertified.

Beyond its applicability to multistate or nationwide classes, the Mazza decision is useful in challenging predominance based upon its holding that a smaller class of California consumers could not be certified. Individualized issues of reliance on the alleged misleading advertising predominated, the court said. In part, the court reasoned that reliance could not be presumed because it was likely that many purported members were never exposed to the allegedly misleading advertising and, therefore, could not have relied upon such advertising in making their purchasing decisions.

Of course, the application of the Mazza decision extends far beyond cases involving automobiles and other durable goods and is equally applicable to food false labeling actions. Indeed, in the recent case of Holt v. Globalinx Pet LLC (C.D. Cal. Jan. 30, 2014), a California district court judge, relying heavily on Mazza, denied certification of several nationwide classes of consumers who claimed to have purchased allegedly tainted dog treats, ruling that the proposed class did not meet Rule 23’s predominance and superiority requirements.

Thus, whether faced with a nationwide, multistate or single-state class action lawsuit of consumers of automobiles, air compressors or aspartame, Mazza presents another strong tool for defendants against class certification on predominance grounds. Recent court decisions, however, suggest that care should be taken when making predominance-based arguments in opposing class certification. For example, federal courts have allowed class certification notwithstanding Mazza-based arguments where the defendant failed to satisfy its burden of showing that the laws of various states applicable to the action were materially different. (Bruno v. Eckhart Corp., C.D. Cal. 2012).

Thus, rather than simply citing Mazza, defendants should take great care in performing a “choice of law” analysis, identifying the differences in the states’ laws that may be applicable to the claims and painstakingly articulating how the differences in those states’ laws preclude a finding of predominance.

Defending food and beverage false labeling claims has evolved into a particularly specialized area of litigation. And although each case must be carefully analyzed to identify the defenses available to manufacturers and their insurers, the foregoing represent some of the key battlegrounds routinely encountered in the war against food false labeling claims.

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash  Bomb Cyclone Expected This Weekend for East Coast, Southern U.S.

Bomb Cyclone Expected This Weekend for East Coast, Southern U.S.  Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs