Even workers toiling at desk jobs and other seemingly safe professions are facing stresses that are hazardous to their health, including long hours, job insecurity and lack of work-life balance issues, a new study reveals.

These types of workplace stress contribute to at least 120,000 deaths each year and account for up to $190 billion in health care costs, according to research by two Stanford professors and a former Stanford doctoral student now at Harvard Business School, announced in late February.

“The deaths are comparable to the fourth- and fifth-largest causes of death in the country: heart disease and accidents,” said Stefanos A. Zenios, Professor of Operations, Information, and Technology and Professor of Health Care Management at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, in a statement announcing the results. “It’s more than deaths from diabetes, Alzheimer’s or influenza.”

“The deaths are comparable to the fourth- and fifth-largest causes of death in the country: heart disease and accidents,” said Stefanos A. Zenios, Professor of Operations, Information, and Technology and Professor of Health Care Management at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, in a statement announcing the results. “It’s more than deaths from diabetes, Alzheimer’s or influenza.”

Zenios and colleague Jeffrey Pfeffer, a Stanford professor of organizational behavior, together with Joel Goh of Harvard Business School, conducted a meta-analysis of 228 studies, examining how 10 common workplace stressors affect a person’s health:

- Job insecurity

- Long work hours

- Low social support at work

- Low job control

- Secondhand smoke exposure

- Unemployment

- Exposure to shift work

- High job demands

- Low organizational justice

- No health insurance

Overall, the 10 stressors taken together increase national health care costs by 5-8 percent, they found.

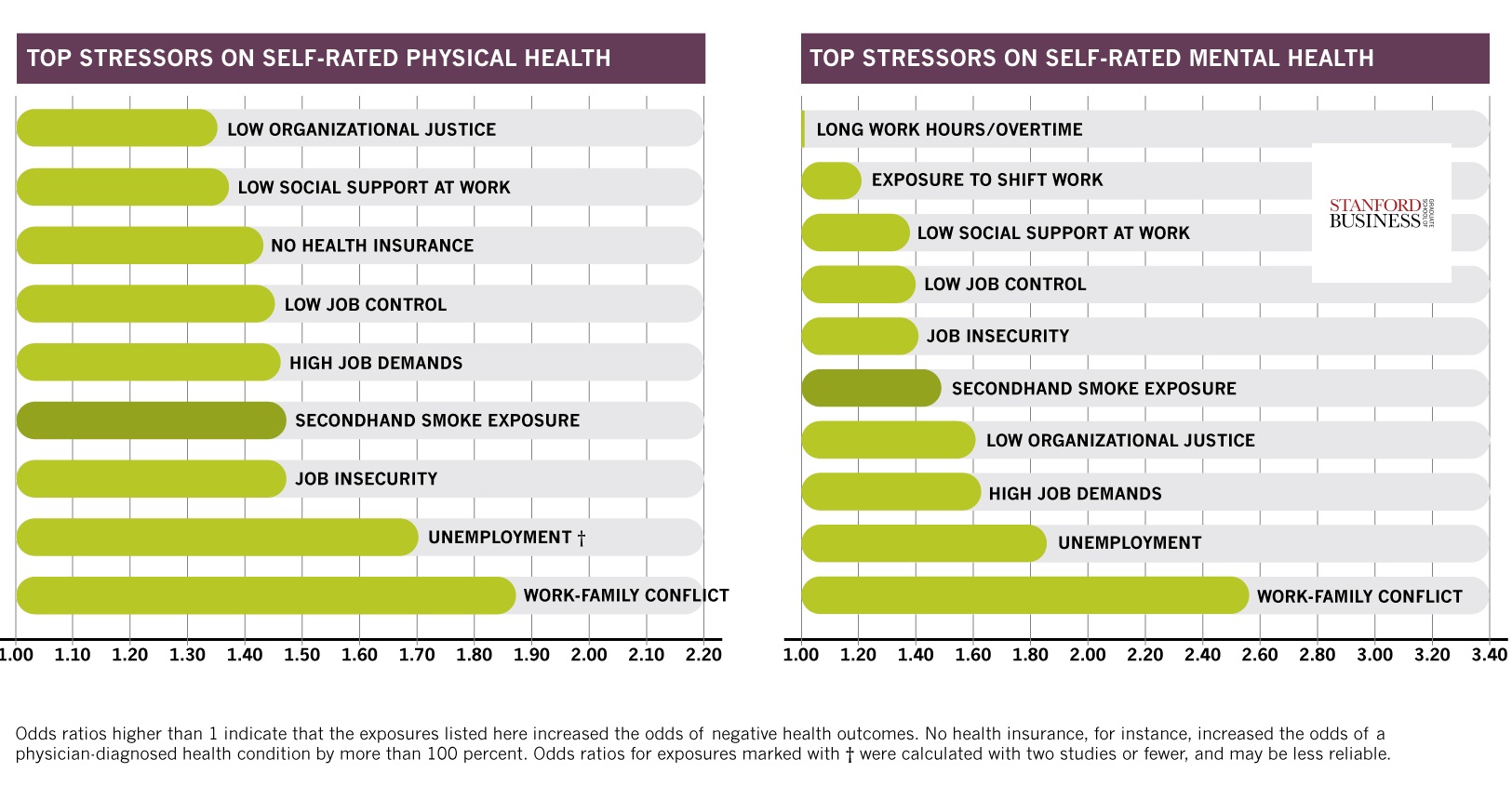

Job insecurity increases the odds of workers self-reporting poor physical health by 50 percent and poor mental health by about 40 percent, according to charts presented with an announcement of the findings.

The most significant stressor is work-family conflict, increasing the odds of self-reported physical illness by roughly 85 percent.

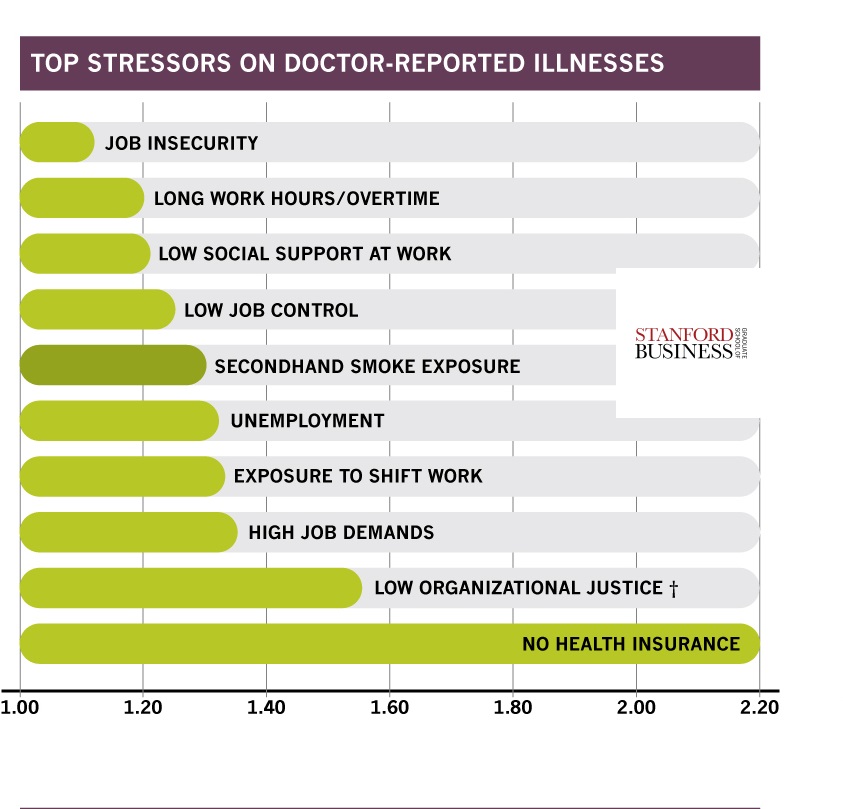

Far and away, the most significant stress factor associated with doctor-reported illnesses is lack of health insurance. “No health insurance increased the odds of a physician-diagnosed health condition by more than 100 percent,” the researchers found.

Low organizational justice and high job demands are also associated with more doctor reports of illness.

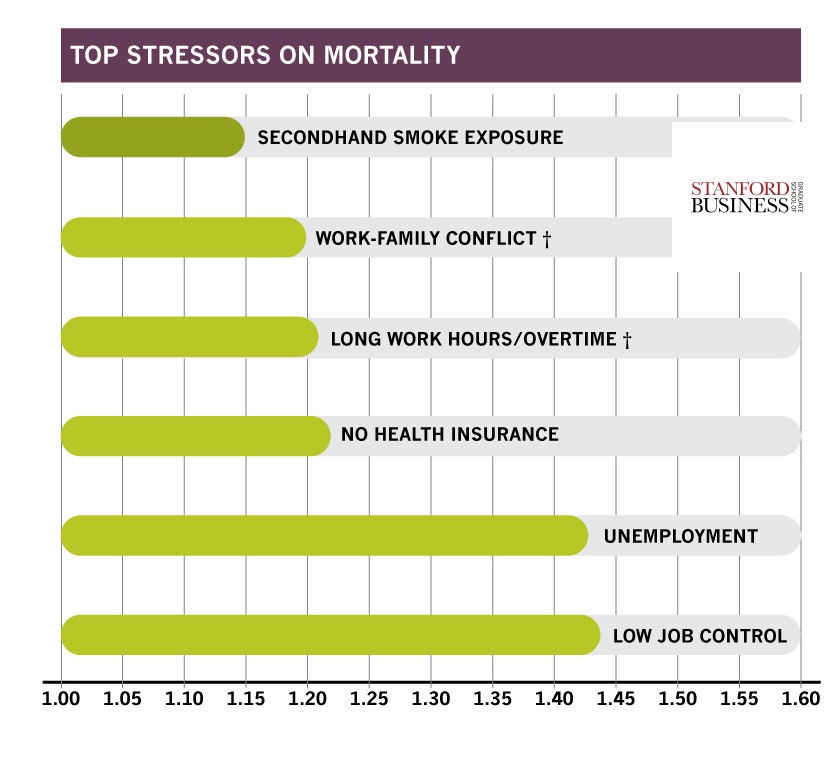

In addition, long work hours increased mortality by almost 20 percent, the researchers said in a statement titled “Why Your Workplace Might Be Killing You.”

What else might kill you?

The most significant stressor on mortality among the 10 analyzed by the researchers is low job control, which increased mortality rates by almost 45 percent.

Pulling the finding together, the researchers note that:

- The stressor with the biggest impact overall is lack of health insurance. It ranks high in both increasing mortality and health care costs.

- Another big driver of early death is economic insecurity, captured in part by unemployment, layoffs and low job control.

Pfeffer said that while the ramifications of being uninsured came as no surprise, what did surprise the team was the high impact of psychological stressors.

Work-family conflict and work injustice had just as much impact on health as long work hours or shift work.

For example, employees who reported that their work demands prevented them from meeting their family obligations or vice versa were 90 percent more likely to self-report poor physical health, the researchers noted. And employees who perceive their workplaces as being unfair are about 50 percent more likely to develop a physician-diagnosed condition.

The researchers acknowledge that their study has limitations. Chief among them is the fact that they are unable to make strong causal inference linking these stressors to poor health because the studies they used are observational.

“It is association—it doesn’t mean that there’s causation,” Zenios said. “There may be other factors going on.”

Fixing Wellness Programs

Pfeffer believes the findings have implications for the design of wellness programs. Organizations, including Stanford, institute wellness programs that focus on encouraging employees to eat better or exercise more. Meanwhile, these companies overlook the atmosphere of workplace setting itself, he noted.

“Lots of research shows that your tendency to overeat, overdrink and take drugs is affected by your workplace,” he said. “When people like their lives, and that includes work life, they will do a better job of taking care of themselves. When they don’t like their lives, they don’t.”

Smoking cessation programs or incentives to lose weight focus on individual behavior and ignore management practices that create stress and set the context for employee choices.

Beyond the workplace, Pfeffer advocated government tax incentives that would encourage employers to offer more work-family balance or reduce layoffs. “Nonregulatory actions like guidelines or best practices might also prove fruitful” at the government level, he suggested.

Source: Stanford Graduate School of Business

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash