By the spring of this year, the financial press was filled with articles documenting the pause in numerical and medical inflation. But few outside the insurance industry are discussing—or maybe even aware of—social inflation, which is climbing.

Executive Summary

Social inflation, marked by a rising propensity to sue and higher jury verdicts, is a growing threat to the property/casualty insurance industry’s profitability, according to Assured Research Analysts William Wilt and Alan Zimmermann. Here, they describe three relevant trends pushing social inflation to levels not seen in two decades. Among them is increased lawyer advertising fueling litigation activity in several U.S. metro areas.An inflection point in loss cost trends, fueled by social inflation, could actually be the No. 1 threat to the property/casualty insurance industry’s already marginal profitability, according to a June 2017 Assured Research report. Evidence is mounting that social inflation is rearing its head after nearly a 20-year hiatus.

What Is Social Inflation?

There is no one commonly accepted definition of social inflation, but most would agree that it contains elements of changes in the propensity of the legal system to interpret contracts broadly or to reward plaintiffs with rising levels of awards. Social inflation also encompasses the trend of claimants to involve an attorney in their claim—or to file a claim or lawsuit in the first place.

With exceptions in a few segments, social inflation has been benign since the late 1990s and early 2000s. It has dropped out of most actuarial datasets, we suspect, and its re-emergence could lead to reserve deficiencies and inadequate pricing of new and renewal business.

In our June 2017 research report, Assured Research analyzes three relevant trends, providing hard evidence that the risks of social inflation are real and deserving of attention by all insurance professionals.

- Judicial vacancies at federal and state levels.

- Legal services advertising.

- Growth in the litigation funding asset class.

We summarize some of the highlights of our analysis here. (The full report is available to Assured Research subscribers at www.assuredresearch.com.)

Trump Can’t Control Social Inflation: Judicial Vacancy Analysis

P/C insurance professionals have long believed that social inflation is better controlled under Republican presidents. This stems from the view that vacancies in the federal judiciary will be filled with conservative judges likely to stay within the four corners of the contract when hearing cases with ramifications for P/C insurers.

Based on our examination of federal and state courts as well as channel-checking with knowledgeable professionals, we have concluded that state courts matter more to insurers than do federal courts.

Federal courts are important, of course, particularly in social matters such as immigration, privacy and the role of the federal government in the lives of citizens. And interestingly, insurance coverage matters are often tried in federal courts, although our sources suggest that the judge’s political stripes probably matter less in this area since the decisions are largely technical.

But to our main point, some may hear the large number of federal vacancies the Trump administration has to fill—129 current vacancies, plus 22 future ones—and be too quick to assume that the current, pro-business president can entirely remake the federal judiciary. It’s not that simple.

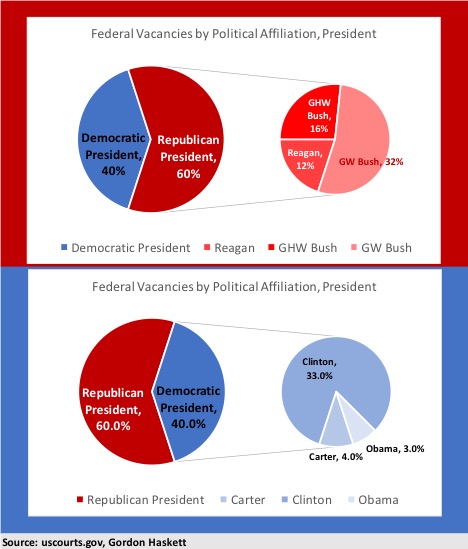

We scrubbed data from the U.S. Court system and found that 60 percent of those 151 total vacancies were created by judges appointed by Republican presidents. The pie charts below provide additional color showing vacancies by past presidential appointment. Again, our main message is not that federal appointments don’t matter to businesses and insurers but rather that even though the president has many vacancies to fill, the majority are replacements of Republican-appointed judges.

Advertising for Legal Services Is Rising

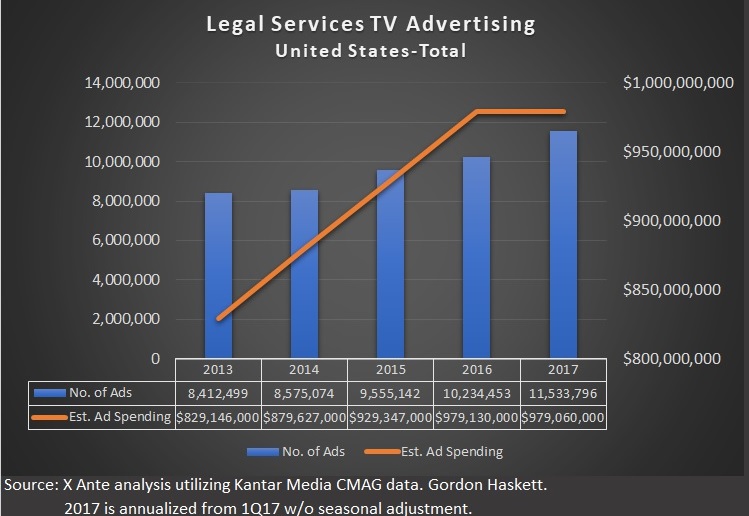

Many professionals will have heard insurance executives comment on the rising propensity to sue and higher jury verdicts adversely affecting insurance costs, particularly in major metropolitan areas. Proprietary data, supplied by mass tort intelligence firm X ANTE, reveals that accelerating advertising spending may be fueling those trends.

From 2013-2016, both the number of ads and dollars spent were up about 6 percent per year across the United States.

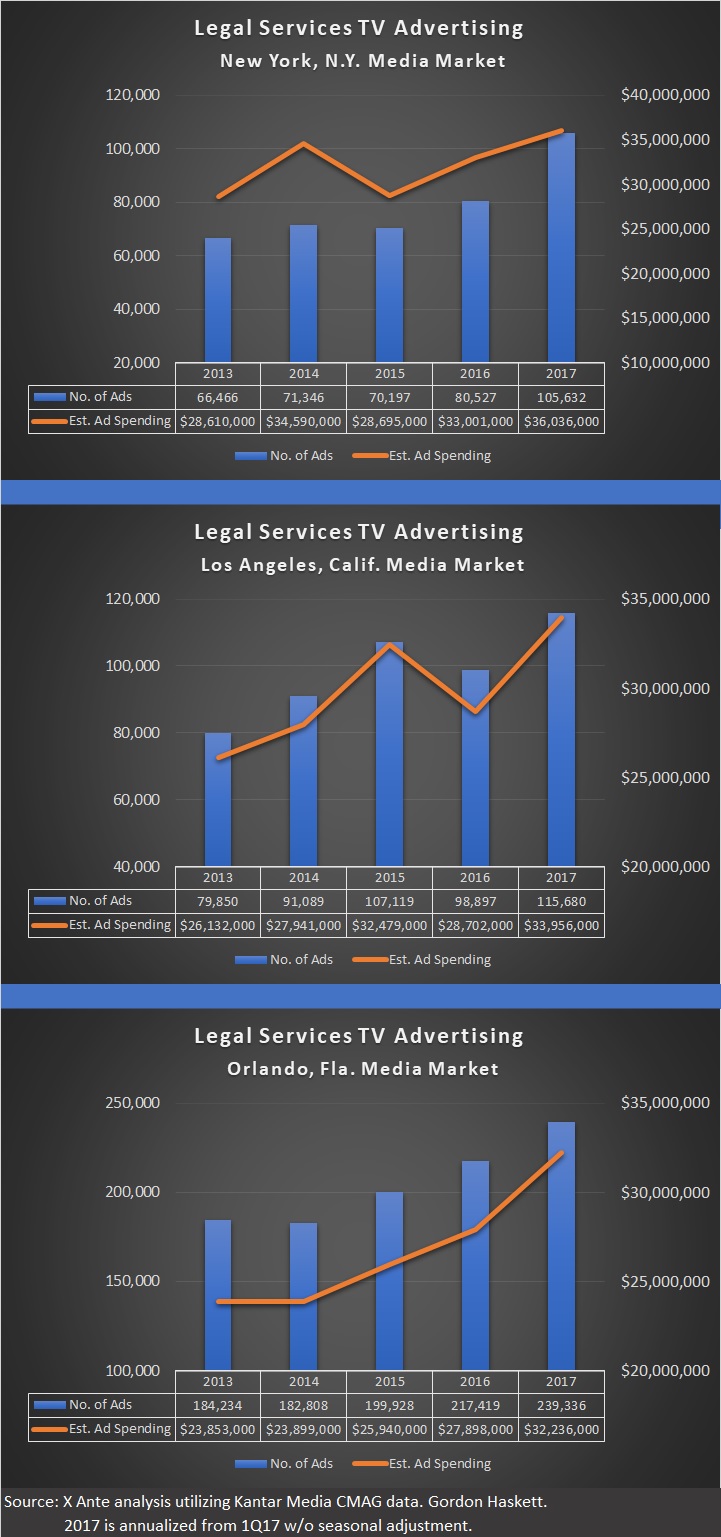

Some individual metropolitan areas show even stronger trends. Insurer RLI specifically called out the New York/New Jersey market in its first-quarter conference call (see related article: “What Insurance Execs Are Saying.”) X Ante’s analysis shows what may have sparked the commentary. From 2013-2017 (full-year projected from first quarter), the number of ads jumped 12 percent per annum and spending rose 6 percent per year in the New York media market.

Los Angeles isn’t far behind, and even in a smaller but rapidly growing media market, such as Orlando, Fla., advertising trends are moving up. For Los Angeles, the number of ads grew 10 percent per year, on average, and spending rose 7 percent. In Orlando, the comparable figures were 7 percent per annum for the number of ads and 8 percent for spending dollars.

Experience has taught us to never underestimate the plaintiffs’ bar. Where advertising for legal services is on the rise, we assume that is because the law firms are experiencing and anticipate a favorable return on their investment—rarely good news for insurers.

And we suspect the growth in advertising for legal services is connected to rapid growth in the assets backing third-party litigation funding—the third leg of social inflation.

Out of the Shadows: Third-Party Litigation Funding on the Rise

We believe third-party litigation funding will become a big business in the United States for the simple reason that it fits the needs of multiple parties: plaintiffs, law firms and long-term investors.

Litigation funding is a practice whereby specialized investment firms provide funds to either plaintiffs or their lawyers to pursue litigation. The payoff comes if the plaintiff wins a monetary reward, in which case the investor gets a percentage of the return.

When we first looked at the business two years ago, the emphasis was chiefly aimed at single-case plaintiffs in exchange for a percentage of any awards. In an important development, litigation funding specialists have been raising outside funds, thus increasing the amounts available for investment.

Now, with more funds available, the investment emphasis is on entire litigation portfolios whereby the funding companies advance funds to law firms in return for a percentage of the returns on all the litigation across the law firm’s book of business.

This strategy not only diversifies the risk in the litigation funding firm’s portfolio but also allows for much larger amounts of money to be put to work.

There have been numerous fund raises in the last few years. Examples are:

- Gerchen Keller Capital, which was acquired last December by London-based Burford Capital, the largest litigation funder, has raised over $1.0 billion in the three years since its founding.

- IMF Bentham, an Australian firm that has been steadily increasing its presence in the U.S., recently teamed up with a subsidiary of Fortress Investment Group to create a $150 million fund that could be expanded to $200 million under certain circumstances.

- Canadian firm Balmoral Wood Litigation Finance is in the process of raising a $150 million fund that would invest across a spectrum of litigation specialists, exemplifying the growing maturity of the business.

We also expect litigation funding to expand because it fits the changing economics of law firms. This growing asset class provides working capital to law firms, which is used to finance increasingly complex and research-intensive lawsuits.

Over the long term, insurers and plaintiffs’ firms have a symbiotic relationship; activity by plaintiff firms drives demand for insurers’ products. But in the near term, well-funded law firms could be a thorn in the sides of insurers, leading to more claims and more costly claims.

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes  Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook  What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll